The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974 film)

| The Taking of Pelham One Two Three | |

|---|---|

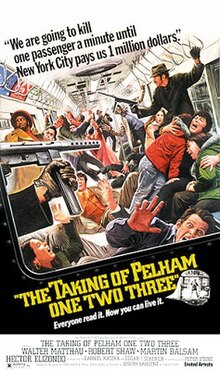

Original film poster by Mort Künstler | |

| Directed by | Joseph Sargent |

| Screenplay by | Peter Stone |

| Based on | The Taking of Pelham One Two Three 1973 novel by John Godey |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Owen Roizman |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | David Shire |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.8 million[2] |

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (also known as The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3) is a 1974 American crime drama film[1] directed by Joseph Sargent, produced by Gabriel Katzka and Edgar J. Scherick, and starring Walter Matthau, Robert Shaw, Martin Balsam and Héctor Elizondo.[3] Peter Stone adapted the screenplay[3] from the 1973 novel of the same name written by Morton Freedgood under the pen name John Godey.

The title is derived from the train's radio call sign, which is based on where and when the train began its run; in this case, the train originated at the Pelham Bay Park station in the Bronx at 1:23 p.m. For several years after the film was released, the New York City Transit Authority would not schedule any train to leave Pelham Bay Park station at 1:23.[4]

The film received critical acclaim. Several critics called it one of 1974's finest films, and it was a box-office success.[5] As in the novel, the film follows a group of criminals who hijack a New York City Subway car and hold the passengers for ransom. Musically, it features "one of the best and most inventive thriller scores of the 1970s".[6] It was remade in 1998 as a television film and in 2009 as a theatrical film.

Plot

[edit]In New York City, four men wearing similar disguises and carrying concealed weapons board the same downtown 6 train, "Pelham 1-2-3", at different stations. Using the codenames Mr. Blue, Mr. Green, Mr. Grey and Mr. Brown, they take 18 people, including the conductor and an undercover police officer, hostage in the front car.

Communicating over the radio with New York City Transit Police lieutenant Zachary Garber, Mr. Blue demands that a $1 million ransom be delivered within exactly one hour or he will kill one hostage for every minute it is late. Mr. Green sneezes periodically, to which Garber always responds, "Gesundheit". Garber, Lt. Patrone and others cooperate while speculating about the hijackers' escape plan. Garber surmises that one hijacker must be a former motorman because they were able to uncouple the head car and park it farther down the tunnel below 28th Street.

Conversations between the hijackers reveal that Mr. Blue is a former British Army colonel and was a mercenary in Africa; Mr. Green was a motorman caught in a drug bust; and Mr. Blue does not trust Mr. Grey, who was ousted from the Mafia for being erratic. Unexpectedly, Mr. Grey shoots and kills transit supervisor Caz Dolowicz, sent from Grand Central, as he approaches the stalled train.

The ransom is transported uptown in a speeding police car that crashes well before arriving at 28th Street. As the deadline is reached, Garber bluffs Mr. Blue by claiming that the money has reached the station entrance and just has to be walked down the tunnel to the train. Meanwhile, a police motorcycle arrives with the ransom. As two patrolmen carry the money down the tunnel, one of the many police snipers in the tunnel shoots at Mr. Brown, and the hijackers exchange gunfire with the police. In retaliation, Mr. Blue kills the conductor.

The money is delivered and divided among the hijackers. Mr. Blue orders Garber to restore power to the subway line, set the signals to green all the way to South Ferry, and clear the police from stations along the route. Before the process is complete, however, Mr. Green moves the train farther south. When Garber becomes alarmed, Mr. Blue explains that he wanted more distance from the police inside the tunnel.

The hijackers override the dead man's switch so that the train will run without anyone at the controls. Garber joins Inspector Daniels above ground where the train stopped. The hijackers set the train in motion and get off. As they walk to the tunnel's emergency exit, the undercover officer jumps off the train and hides between the rails. Unaware that the hijackers have left the train, Garber and Daniels drive south above its route. With no one at the controls, the train gains speed.

The hijackers collect their disguises and weapons for disposal, but Mr. Grey refuses to surrender his gun, resulting in a stand-off with Mr. Blue, who kills him. The undercover officer kills Mr. Brown and exchanges fire with Mr. Blue while Mr. Green escapes through an emergency exit onto the street.

Garber, contemplating the train's suspicious last movement, concludes that the hijackers have bypassed the dead-man feature and are no longer on board. He returns to where the train had stopped, enters the same emergency exit from street level, and confronts Mr. Blue as he is about to kill the undercover officer. With no escape, Mr. Blue electrocutes himself by deliberately placing his foot against the third rail.

Meanwhile, Pelham 123 hurtles through the southbound tunnel. When it enters the South Ferry loop, its speed triggers the automatic safeties. It screeches to a halt, leaving the hostages bruised but safe.

Since none of the three dead hijackers was a motorman, Garber infers that the lone survivor must be. Working their way through a list of recently discharged motormen, Garber and Patrone knock on the door of Harold Longman (Mr. Green). After hastily hiding the loot, Longman lets them in, bluffs his way through their interrogation, and complains indignantly about being suspected. Garber vows to return with a search warrant. As Garber closes the apartment door behind him, Longman sneezes, and Garber reflexively says "Gesundheit", as he had over the radio. Garber re-opens the door and gives Longman a caustic, knowing stare.

Cast

[edit]- Walter Matthau as Lt. Zachary Garber

- Robert Shaw as Mr. Blue

- Martin Balsam as Mr. Green

- Héctor Elizondo as Mr. Grey (as Hector Elizondo)

- Earl Hindman as Mr. Brown

- James Broderick as Denny Doyle

- Dick O'Neill as Correll

- Lee Wallace as the Mayor

- Tony Roberts as Deputy Mayor Warren LaSalle

- Tom Pedi as Caz Dolowicz

- Beatrice Winde as Mrs. Jenkins

- Jerry Stiller as Lt. Rico Patrone

- Nathan George as Patrolman James

- Rudy Bond as Police Commissioner

- Kenneth McMillan as Borough Commander (as Kenneth Mc Millan)

- Doris Roberts as mayor's wife

- Julius Harris as Inspector Daniels

Production

[edit]Godey's novel was published in February 1973 by Putnam, but Palomar Productions had secured the film rights, and Dell had bought the paperback rights months earlier in September 1972. The paperback rights sold for US$450,000 (equivalent to $3.28 million in 2023).[7]

Godey (Morton Freedgood) was a "subway buff".[8] The novel and the film came out during the so-called "Golden Age" of skyjacking in the United States from 1968 through 1979.[citation needed] Additionally, New York City was edging toward a financial crisis; crime had risen citywide, and the subway was perceived as neither safe nor reliable.

At first, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) refused to cooperate with the filmmakers. Godey's novel was more detailed about how the hijackers would accomplish their goal and recognized that the caper's success did not rely solely on defeating the "deadman feature" in the motorman's cab. Screenwriter Stone, however, made a linchpin of the script a fictional override mechanism. Director Sargent explained, "We're making a movie, not a handbook on subway hijacking. ... I must admit the seriousness of Pelham never occurred to me until we got the initial TA reaction. They thought it potentially a stimulant—not to hardened professional criminals like the ones in our movie, but to kooks. Cold professionals can see the absurdities of the plot right off, but kooks don't reason it out. That's why they're kooks. Yes, we gladly gave in about the 'deadman feature'. Any responsible filmmaker would if he stumbled onto something that could spread into a new form of madness."[2]

Sargent said, "It's important that we don't be too plausible. We're counting on the film's style and charm and comedy to say, subliminally at least, 'Don't take us too seriously.'"[2] The credits have a disclaimer that the Transit Authority did not give advice or information for use in the film.

After eight weeks of negotiations, and through the influence of Mayor John Lindsay, the MTA relented but required that the producers take out $20 million in insurance policies, including special "kook coverage" in case the movie inspired a real-life hijacking.[2] This was in addition to a $250,000 fee for use of the track, station, subway cars and TA personnel.

The TA also insisted that no graffiti appear in the film. Graffiti had become increasingly prevalent on trains starting in 1969. Mayor Lindsay had first announced his intention to remove graffiti in 1972,[9] but the last graffiti-covered car was not removed from service until 1989. "New Yorkers are going to hoot when they see our spotless subway cars," Sargent said. "But the TA was adamant on that score. They said to show graffiti would be to glorify it. We argued that it was artistically expressive. But we got nowhere. They said the graffiti fad would be dead by the time the movie got out. I really doubt that."[2]

Other changes included beefing up Matthau's role. In the novel, Garber is the equivalent of the Patrone character in the film. "I like the piece," Matthau said. "It moves swiftly and stays interesting right down to the wire. That's the reason I wanted to do it. The TA inspector I play is really a supporting role—they built it up a bit when I expressed interest in it—but it's still secondary."[2] In the novel, Inspector Daniels confronts Mr. Blue in the tunnel during the climax. Additionally, screenwriter Peter Stone gave the hijackers their color code names, with hats whose colors matched their code names, as well as Longman his telltale cold.

Filming began on November 23, 1973, and was completed in late April 1974.[10] The budget was $3.8 million.[2]

Filming locations

[edit]Production began with scenes inside the subway tunnel. These were filmed over the course of eight weeks on the local tracks of the IND Fulton Street Line at the abandoned Court Street station in Brooklyn. Closed to the public in 1946, it became a filming location and later home to the New York Transit Museum. Among other films, the Court Street station was used for The French Connection (1971), Death Wish (1974), and the 2009 remake of Pelham.

The production company set up chess boards, card tables, and ping pong tables along the Court Street platform for cast and crew recreation between set-ups. Robert Shaw apparently beat all comers in ping pong.[11]

Although this was an abandoned spur of track, passing A, E and GG trains rumbled through adjacent tracks on their regular schedules. Dialogue that was marred by the noise was later post-dubbed. The third rail, which carries 600 volts of direct current, was shut off, and three protective bars were placed against the rail, but the cast and crew were told to treat it as if it were still live. "Those TA people ... are super careful," Sargent said. "They anticipate everything. By the fifth week we were dancing our way through those tunnels like nobody's business. They were expecting that, too. That's when they told us of the fatalities in the tunnels. They're mostly old-timers. The young guys still have a healthy fear of the place."[2]

"There was one scene where Robert Shaw was to step on the third rail," Sargent recalled. "When we were rehearsing the scene, Shaw accidentally stubbed his toe and the sparks from his special-effects boot flew everywhere. He turned white as a sheet. We had eight weeks of that. I think we got out just in time. It was like coal mining."[2]

According to a notation on IMDb[better source needed], the crew wore surgical masks during the tunnel scenes.[11] Shaw's biographer John French reported, "There were rats everywhere and every time someone jumped from the train, or tripped over the lines, clouds of black dust rose into the air, making it impossible to shoot until it had settled."[12]

Matthau, who had one scene in the tunnel, said, "There are bacteria down there that haven't been discovered yet. And bugs. Big ugly bugs from the planet Uranus. They all settled in the New York subway tunnels. I saw one bug mug a guy. I wasn't down there a long time—but long enough to develop the strangest cold I ever had. It stayed in my nose for five days, then went to my throat. Finally I woke up one morning with no voice at all, and they had to shut down for the day."[2]

According to Backstage, the filmmakers were the first to use a "flash" process developed by Movielabs to bring out detail when shooting with low light in the tunnel. The process reportedly increased film speed by two stops. It allowed the filmmakers to use fewer lights and generators, and cut five days out of the schedule.[13]

At least two R22 trains portrayed Pelham 123. As it enters the 28th Street station, the head car is labeled 7339. However, in an early scene at Grand Central, 7339 is seen on the express track across the platform. Later, after being cut from the rest of the train, the head car is labeled 7434.[14] R22 cars first went into service in April 1957, and the vast majority of the 450 cars were scrapped in 1987.

After two months in the tunnel, production moved to Filmways Studios at 246 East 127th Street in East Harlem, where a replica of the Transit Authority's Brooklyn control center was constructed. Built around 1920 as Cosmopolitan Studios, the facility was leased in 1928 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for sound production and purchased by Filmways in 1959. Among later films that were shot there were Butterfield 8 (1960), The Godfather (1972), The Wiz (1978) and Manhattan (1979). The building was demolished in the 1980s.

The exterior street scenes above the hijacked subway train were filmed at the subway entrance at 28th and Park Avenue South in Manhattan. The mayor's residence, Gracie Mansion, was used for exteriors. Wave Hill, a nineteenth-century mansion overlooking the Hudson River in Riverdale, the Bronx, was used for the interior scenes set in Gracie Mansion.[15]

Music

[edit]The score, composed and conducted by David Shire, "layers explosive horn arrangements and serpentine keyboard riffs over a rhythm section that pits hard-grooving basslines against constantly shifting but always insistent layers of percussion".[6] Shire used the 12-tone composition method to create unusual, somewhat dissonant melodic elements.[16]

The soundtrack album was the first CD release by Film Score Monthly and was soon released by Retrograde Records.[16] The end titles contain a more expansive arrangement of the theme, courtesy of Shire's wife at the time, Talia Shire, who suggested that he end the score with a more traditional ode to New York.[17]

Release

[edit]The Taking of Pelham One Two Three was released to theaters on October 2, 1974.[1]

Critical reception

[edit]The film holds a 98% score on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 44 reviews and a weighted average of 8.3/10. The site's consensus reads: "Breezy, thrilling, and quite funny, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three sees Walter Matthau and Robert Shaw pitted against each other in effortlessly high form."[18]

The film was well received by critics. Variety called it "a good action caper", but "the major liability is Peter Stone's screenplay, which develops little interest in either Matthau or Shaw's gang, nor the innocent hostages", who are "simply stereotyped baggage". Although the trade paper complained that the Mayor was "played for silly laughs", it called Shaw "superb in another versatile characterization".[19]

BoxOffice thought that "some of the excitement has been lost" translating the novel to the screen, but "there is entertainment value in Peter Stone's screenplay".[20]

Nora Sayre of The New York Times thought that it captured the mood of New York and New Yorkers. "Throughout there's a skillful balance between the vulnerability of New Yorkers and the drastic, provocative sense of comedy that thrives all over our sidewalks. And the hijacking seems like a perfectly probable event for this town. (Perhaps the only element of fantasy is the implication that the city's departments could function so smoothly together). Meanwhile, the movie adds up to a fine piece of reporting—and it's the only action picture I've seen this year that has a rousing plot."[21]

The film was one of several released that year that gave New York a bad image, including Law and Disorder, Death Wish, Serpico and The Super Cops. Vincent Canby, another critic for The New York Times, wrote, "New York is a mess, say these films. It's run by fools. Its citizens are at the mercy of its criminals who, as often as not, are protected by an unholy alliance of civil libertarians and crooked cops. The air is foul. The traffic impossible. Services are diminishing and the morale is such that ordering a cup of coffee in a diner can turn into a request for a fat lip." But The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, "compared to the general run of New York City films, is practically a tonic, a good-humored, often witty suspense melodrama in which the representatives of law and decency triumph without bending the rules."[22]

The Boston Globe called it "fast, funny and fairly terrifying" and "a nerve-racking ride", and appreciated the "wry humor" of Stone's script. It tapped into a darker reality: "A short time ago subways were safe; today some of them are full of the dark rage of asylums. And who really is to say a Pelham-type incident is out of the question?"[23]

Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "coarse-textured and effective, a cartoon-vivid melodrama and not, it's nice to know, a case study of psychopathic behavior. 'Pelham' is in fact the best to date of the new multiple-jeopardy capers, fresh, lively and suspenseful... . There are some marvelously managed scenes in the subway tunnels and on teeming platforms and at the barricaded street-level entrances. The subway nerve center is fascinating, and indeed one of the pleasures of the film is its glimpse of how things work... . The violence is handled with restraint; the dangers are mixed with raucous humor and what stays clear is that the aim is swift entertainment."[24]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 3 stars out of 4. He praised the film's "unforced realism" and the supporting characters who elevated what could have been a predictable crime thriller: "We care about the people not the plot mechanics. And what could have been formula trash turns out to be fairly classy trash, after all."[25]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune also gave the film 3 stars out of 4, describing it as a "solid new thriller laced with equal amounts of tension and comedy".[26]

Accolades

[edit]- 1976: Nominated, "Best Film Music"—David Shire

- 1976: Nominated, "Best Supporting Actor"—Martin Balsam

Writers Guild of America Award

- 1975: Nominated, "Best Drama Adapted from Another Medium"—Peter Stone

Remakes

[edit]In 1998, the film was remade as a television film with the same title, with Edward James Olmos in the role that Walter Matthau played in the movie, and Vincent D'Onofrio replacing Shaw as the senior hijacker.[citation needed] Although not particularly well received by critics or viewers, this version was reportedly more faithful to the book, although it revised the setting with new technologies.[citation needed] It was filmed in Toronto, Ontario, and is jokingly referred to as “The Taking of Bloor Street 123”.

Another remake, set in post 9/11 New York City, directed by Tony Scott and starring Denzel Washington and John Travolta, was released in 2009 to mixed reviews.[27]

Legacy

[edit]The color-coded thieves' names in Reservoir Dogs was a deliberate homage by Quentin Tarantino to The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Haun, Harry (April 7, 1974). "Matthau Lightens the Suspense in Filming of a N.Y. Subway Hijacking". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 24, 53, 72.

- ^ a b "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ Dwyer, Jim (1991). Subway lives : 24 hours in the life of the New York City subway (1st ed.). New York City: Crown Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0517584453.

- ^ Godey, John (1974). The Taking of Pelham One, Two, Three (1st ed.). New York City: Dell Books. ISBN 978-0440184959. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-09-12.

- ^ a b "Taking of Pellham 123". Allmusic. 2013. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Variety, Sept. 6, 1972 page 60

- ^ The New York Times, 28 Jan 1974. p 29.

- ^ Banks, Alec. "The History of Subway Graffiti in New York City". Rock The Bells. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". Archived from the original on 2018-08-17. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ a b "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974) - Trivia - IMDb". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ French, John. Robert Shaw: The Price of Success. Dean Street Press.

- ^ Backstage, March 1, 1974

- ^ "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974) - Goofs - IMDb". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Daily News, "Will The Real Movie Mayor Stand Up?", February 21, 1974.

- ^ a b "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)". Film Score Monthly. 2013. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Adams, Doug. CD liner notes

- ^ "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ Variety, Oct. 2, 1974, p. 22

- ^ "Feature Reviews: The Taking of Pelham One Two Three". BoxOffice. October 7, 1974.

- ^ Sayre, Nora (October 3, 1974). "'Pelham One Two Three,' Starring Matthau, Catches the City's Mood". The New York Times, Oct. 3, 1974, p. 50.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 10, 1974). "New York's Woes Are Good Box Office". The New York Times, Section 2, p. 1.

- ^ The Boston Globe, Oct. 17, 1974, p. 61

- ^ Champlin, Charles (October 23, 1974). "Taking A-Train—for Keeps". Los Angeles Times, Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 2, 1974). "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (November 11, 1974). "The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 19.

- ^ "The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3 (2009)". Rotten Tomatoes. 2013. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Seelie, Christopher (August 5, 2014). "10 Films That Had The Biggest Influences On Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs".

External links

[edit]- 1974 films

- 1970s action thriller films

- 1970s crime thriller films

- American action thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- Films about extortion

- Films about hijackings

- Films about murderers

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films based on works by Morton Freedgood

- Films directed by Joseph Sargent

- Films scored by David Shire

- Films set on the New York City Subway

- Films about hostage takings

- American police detective films

- United Artists films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- Films about train robbery

- English-language action thriller films

- English-language crime thriller films