Jean Harlow

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Jean Harlow | |

|---|---|

Harlow, 1930s | |

| Born | Harlean Harlow Carpenter March 3, 1911 Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | June 7, 1937 (aged 26) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1928–1937 |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Charles McGrew

(m. 1927; div. 1929) |

| Partner | William Powell (1934–1937) |

| Signature | |

| |

Jean Harlow (born Harlean Harlow Carpenter; March 3, 1911 – June 7, 1937) was an American actress. Spotted, so goes a believable story, by a casting director named Ryan in a parking lot at Fox Studios in February of 1928 - still a few days before she turned 17 - Harlean attracted attention with her spectacular natural beauty, petite frame, green eyes, and natural ash blonde hair. Repeatedly insisting she had no interest in acting in the movies, she finally accepted a letter of recommendation to Central Casting. She took the letter home and dropped it in a drawer and was only, finally, goaded into signing up for work as an extra by her social friends and her mother. Immediately popular for her distinctive beauty as a background extra, Harlean, now going by the name Jean Harlow, landed a brief contract with Hal Roach, appearing in a few Laurel and Hardy shorts. Cast with top billing and her likeness on the posters and advertisements, she exploded into Howard Hughes' wartime airplane epic, Hell's Angels, and after a few more shallow and stereotyped roles, finally arrived at MGM, there to become one of its most popular box office attractions. So convincing was she at playing disreputable tramps or gold diggers on film, she was personally named in 1934 as one of two particularly conspicuous examples of amoral and irresponsible movie making by the newly formed Catholic Legion of Decency. The other was the outrageously raunchy Mae West. The two actresses in real life could not have been more different. Quickly blooming into a smooth, natural, full spectrum actress, she played strong and virtuous women in ten of her last thirteen pictures. Harlow was in the film industry for only nine years, but she became one of Hollywood's biggest movie stars, whose image in the public eye has endured. In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked Harlow number 22 on its greatest female screen legends list.[1]

Early life

[edit]Harlow was born Harlean Harlow Carpenter[2] in a house located at 3344 Olive Street in Kansas City, Missouri.[3]

Her father, Mont Clair Carpenter (1877–1974), son of Abraham L. Carpenter and Dianna (née Beal), was a dentist who attended dental school in Kansas City. He was from a working-class background.[4] Her mother, Jean Poe Carpenter (née Harlow; 1891–1958), was the daughter of wealthy real estate broker Skip Harlow and his wife, Ella Harlow (née Williams). In 1908, Skip Harlow arranged his daughter's marriage to Mont Clair Carpenter. She was underage at the time and grew resentful and unhappy in the marriage, but the Carpenters remained together living in a Kansas City house owned by her father.[5]

Harlean's family called her "Baby," a nickname to which she was accustomed and which endured for the rest of her life. It was not until she was five years old that she learned her real name was Harlean, when staff and students at Miss Barstow's Finishing School for Girls used the name.[6] Harlean was always very close to her mother, who was extremely protective. Her mother was reported to have instilled a sense in her daughter that she owed everything she had to her; "She was always all mine!", Mama Jean said of her daughter in interviews.[7] Jean Carpenter was later known by "Mama Jean" when Harlean achieved star status as Jean Harlow.

When Harlean was at finishing school, her mother filed for a divorce. On September 29, 1922, the uncontested divorce was finalized, giving sole custody of Harlean to her mother. Although Harlean loved her father, she did not see him often after the divorce.[8]

In 1923, the 32-year-old Jean Carpenter took her daughter and moved to Hollywood in hopes of becoming an actress, but was told that she was too old to begin a film career.[9] Harlean was enrolled at the Hollywood School for Girls, where she met Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Joel McCrea, and Irene Mayer Selznick, but dropped out at the age of 14, in the spring of 1925.[10]

With their finances dwindling, Jean and Harlean moved back to Kansas City after Skip Harlow issued an ultimatum that he would disinherit his daughter if they did not return. Several weeks later, Skip sent his granddaughter to summer camp at Camp Cha-Ton-Ka, in Michigamme, Michigan, where she became ill with scarlet fever. Jean Carpenter traveled to Michigan to care for Harlean, rowing herself across the lake to the camp, but was told that she could not see her daughter.[11]

Harlean next attended the Ferry Hall School (now Lake Forest Academy) in Lake Forest, Illinois. Jean Carpenter had an ulterior motive for her daughter's attendance at this particular school: It was close to the Chicago home of her boyfriend, Marino Bello.[12]

First marriage

[edit]During Harlow's freshman year at the school, she was paired with a "big sister" from the senior class who introduced her to 19-year-old Charles "Chuck" Fremont McGrew III, an heir to a large fortune. By the fall of 1926, Harlow and Chuck were dating seriously, and they were married in 1928.[13] Jean Carpenter was also married that same year to Marino Bello, on January 18. However, Harlow did not attend her mother's wedding.[14]

In 1928, two months after the wedding, Chuck McGrew turned 21 and received part of his inheritance. The couple left Chicago and moved to Los Angeles, settling into a home in Beverly Hills, where Harlow thrived as a wealthy socialite. McGrew hoped to distance Harlow from her mother with the move. Neither Chuck nor Harlow worked during this time, and both were considered heavy drinkers.[15]

Career

[edit]1928–1929: Work as an extra

[edit]While living in Los Angeles, Harlean befriended a young aspiring actress named Rosalie Roy. Not owning a car herself, Rosalie asked Harlean to drive her to Fox Studios for an appointment. While waiting for Rosalie, Harlean was noticed and approached by Fox executives, whom she told she was not interested. Nevertheless, she was given letters of introduction to Central Casting. A few days later, Rosalie Roy bet Harlean that she did not have the nerve to go in for an audition. Unwilling to lose a wager and pressed by her enthusiastic mother who had followed her daughter to Los Angeles by this time, Harlean went to Central Casting and signed in under her mother's maiden name, Jean Harlow.[16]

After several calls from casting and a number of job offers rejected by Harlean, Mother Jean finally pressed her into accepting work at the studio. Harlean appeared in her first film, Honor Bound (1928), as an unbilled "extra" for $7 a day (equivalent to approximately $124 in 2023[17] dollars) and a box lunch, common pay for such work.[18][19] This led to a wage increase to $10 per day and small parts in feature films such as Moran of the Marines (1928) and the Charley Chase lost film Chasing Husbands (1928).[19] In December 1928, Harlean as Jean Harlow signed a five-year contract with Hal Roach Studios for $100 per week.[20] She had small roles in the 1929 Laurel and Hardy shorts: Double Whoopee, Liberty and Bacon Grabbers, the last giving her a costarring credit.[21][22]

In March 1929, she parted with Hal Roach, who tore up her contract after Harlow told him, "It's breaking up my marriage, what can I do?"[23] In June 1929, Harlow separated from her husband and moved in with Mother Jean and Bello.[23] After her separation from McGrew, Harlow continued working as an "extra" in such films as This Thing Called Love, Close Harmony, and The Love Parade (all 1929), until she landed her first speaking role in the Clara Bow film The Saturday Night Kid.[24][22] Harlow and her husband divorced in 1929.[25]

1929–1932: Platinum blonde star

[edit]In late 1929, Harlow was spotted by Ben Lyon, an actor filming Howard Hughes' Hell's Angels;[26] another account gives Angels head cameraman Arthur Landau as the man who spotted and suggested her to Hughes.[27] Hughes was reshooting most of his originally silent film with sound and needed an actress to replace Greta Nissen, whose Norwegian accent was undesirable for her character. Harlow screen-tested for Hughes, who gave her the part. On October 24, 1929, Harlow signed a five-year contract with Hughes, paying $100-per-week (equivalent to approximately $1,774 in 2023[17] dollars).[28][29]

During filming of Hells Angels, Harlow met MGM executive Paul Bern, her future husband, for the first time.

Hell's Angels premiered in Hollywood at Grauman's Chinese Theatre on May 27, 1930, and became the highest-grossing film of that year, besting even Greta Garbo's talkie debut in Anna Christie. Hell's Angels made Harlow an international star. Though she was popular with audiences, the critics were less than enthusiastic.[30] The New Yorker called her performance "plain awful",[31] though Variety magazine conceded, "It doesn't matter what degree of talent she possesses ... nobody ever starved possessing what she's got."[30]

In spite of her relative success with Hell's Angels, Harlow again found herself in the role of "uncredited extra" in the Charlie Chaplin film City Lights (1931), though her appearance did not make the final cut.[32][33] With no other projects planned for Harlow at the time, Hughes decided to send her to New York, Seattle, and Kansas City for Hell's Angels premieres.[34] In 1931, his Caddo Company loaned her out to other studios, where she gained more attention by appearing in The Secret Six, with Wallace Beery and Clark Gable; Iron Man, with Lew Ayres and Robert Armstrong; and The Public Enemy, with James Cagney. Even though the successes of these films ranged from moderate to hit, Harlow's acting ability was mocked by critics.[35] Hughes sent her on a brief publicity tour in order to bolster her career, but this was not a success as Harlow dreaded making personal appearances.[36]

Harlow briefly dated gangster Abner Zwillman, who bought her a jeweled bracelet and a red Cadillac, and made a large cash loan to studio head Harry Cohn to obtain a two-picture deal for her at Columbia Pictures. The relationship ended when he reportedly referred to her in derogatory and vulgar terms when speaking to other associated crime figures, as revealed in secret surveillance recordings.[37][38][39]

Columbia Pictures first cast Harlow in a Frank Capra film with Loretta Young, originally titled Gallagher for Young's lead character but renamed Platinum Blonde to capitalize on Hughes' publicity of Harlow's "platinum" hair color.[40][41] Though Harlow denied her hair was bleached,[42] the platinum blonde color was reportedly achieved with a weekly application of ammonia, Clorox bleach, and Lux soap flakes.[43] This process weakened and damaged Harlow's naturally ash-blonde hair.[44] Many female fans began dyeing their hair to match hers and Hughes' team organized a series of "Platinum Blonde" clubs across the nation offering a prize of $10,000 to any beautician who could match Harlow's shade.[40] No one could, and the prize went unclaimed, but the publicity scheme worked and the "Platinum Blonde" nickname stuck with Harlow. Her second film for that studio was Three Wise Girls (1932), with Mae Clarke and Walter Byron, in which she was top billed for the first time.[45]

Paul Bern then arranged with Hughes to borrow her for MGM's The Beast of the City (1932), co-starring Walter Huston. After filming, Bern booked a 10-week personal-appearance tour on the East Coast. To the surprise of many, especially Harlow herself, she packed every theater in which she appeared, often appearing in a single venue for several nights. Despite critical disparagement and poor roles, Harlow's popularity and following were large and growing, and in February 1932, the tour was extended by six weeks.[46]

According to Fay Wray, who played Ann Darrow in RKO Pictures's King Kong (1933), Harlow was the original choice to play the screaming blonde heroine, but was under an exclusive contract with MGM during the film's pre-production phase—and the part went to Wray, a brunette who had to wear a blonde wig.[47]

When mobster Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel came to Hollywood to expand casino operations, Harlow became the informal godmother of Siegel's eldest daughter, Millicent, when the family lived in Beverly Hills.[48][49][50][51]

1932–1937: Successful actress at MGM

[edit]Paul Bern was now romantically involved with Harlow and spoke to Louis B. Mayer about buying her contract with Hughes and signing her to MGM, but Mayer declined. MGM's leading ladies were presented as elegant, and Harlow's screen persona was not so to Mayer. Bern then began urging close friend Irving Thalberg, production head of MGM, to sign Harlow, noting her popularity and established image. After initial reluctance Thalberg agreed, and on March 3, 1932, Harlow's 21st birthday, Bern called her with the news that MGM had purchased her contract from Hughes for $30,000. Harlow officially joined the studio on April 20, 1932.[52]

At MGM, Harlow was given superior movie roles to show off her looks and nascent comedic talent. Though her screen persona changed dramatically during her career, one constant was her sense of humor. In 1932, she starred in the comedy Red-Headed Woman for which she received $1,250 a week. It was the first film in which she "resembles something of an actress", portraying a woman who is successful at being amoral in a film that does not moralize or punish the character for her behavior.[53] The film is often noted as being one of the few films in which Harlow did not appear with platinum blonde hair; she wore a red wig for the role.[44][54] While Harlow was filming Red-Headed Woman, actress Anita Page passed her on the studio lot without acknowledging her. She later told Page that the snub had caused her to cry until she saw herself, noticed the red wig, and burst out laughing when she realized Page had not recognized her.[55] "That shows you how sensitive she was", Page said. "She was a lovely person in so many ways."[56]

She next starred in Red Dust, her second film with Clark Gable. Harlow and Gable worked well together and co-starred in a total of six films.[57] She was also paired multiple times with Spencer Tracy and William Powell. MGM began trying to distinguish Harlow's public persona from her screen characters by putting out press releases that her childhood surname was not the common 'Carpenter' but the chic 'Carpentiér', claiming that writer Edgar Allan Poe was one of her ancestors and publishing photographs of her doing charity work to change her image to that of an all-American woman. This transformation proved difficult; once, Harlow was heard muttering, "My God, must I always wear a low-cut dress to be important?"[58]

During the making of Red Dust, Bern—her husband of two months—was found dead at their home; this created a lasting scandal. Initially, Harlow was suspected of killing Bern,[59] but his death was officially ruled a suicide by self-inflicted gunshot wound. Louis B. Mayer feared negative publicity from the incident and intended to replace Harlow in the film, offering the role to Tallulah Bankhead. Bankhead was appalled by the offer and wrote in her autobiography, "To damn the radiant Jean for the misfortune of another would be one of the shabbiest acts of all time. I told Mr. Mayer as much." Harlow kept silent, survived the ordeal, and became more popular than ever. A 2009 biography of Bern asserted that Bern was, in fact, murdered by a former lover and the crime scene re-arranged by MGM executives to make it appear Bern had killed himself.[60]

After Bern's death, Harlow began an indiscreet affair with boxer Max Baer who, though separated from his wife Dorothy Dunbar, was threatened with divorce proceedings naming Harlow as a co-respondent for alienation of affection, a legal term for adultery. After Bern's death, the studio did not want another scandal and defused the situation by arranging a marriage between Harlow and cinematographer Harold Rosson. Rosson and Harlow were friends, and Rosson went along with the plan. They quietly divorced eight months later.[61][62]

By 1933, MGM realized the value of the Harlow-Gable team with Red Dust and paired them again in Hold Your Man (1933), which was also a box-office success. In the same year, she played the adulterous wife of Wallace Beery in the all-star comedy-drama Dinner at Eight,[4] and played a pressured Hollywood film star in the screwball comedy Bombshell with Lee Tracy and Franchot Tone. The film has been said to be based on Harlow's own life or that of 1920s "It girl" Clara Bow.[63]

The following year, she was teamed with Lionel Barrymore and Tone in The Girl from Missouri (1934). The film was the studio's attempt to soften Harlow's image, but suffered from censorship problems, so much so that its original title, Born to Be Kissed, had to be changed.[64]

After the hit Hold Your Man, MGM cast the Harlow-Gable team in two more successful films: China Seas (1935), with Wallace Beery and Rosalind Russell;[65] and Wife vs. Secretary (1936), with Myrna Loy and James Stewart.[66] Stewart later spoke of a scene in a car with Harlow in Wife vs. Secretary, saying, "Clarence Brown, the director, wasn't too pleased by the way I did the smooching. He made us repeat the scene about half a dozen times ... I botched it up on purpose. That Jean Harlow sure was a good kisser. I realized that until then, I had never been really kissed."[67]

Harlow was consistently voted one of the strongest box office draws in the United States from 1933 onward, often outranking her female colleagues at MGM in audience popularity polls. By the mid-1930s, she was one of the biggest stars in the US, and, it was hoped, MGM's next Greta Garbo. Still young, her star continued to rise while the popularity of other female stars at MGM, such as Garbo, Joan Crawford and Norma Shearer, waned. Harlow's movies continued to make huge profits at the box office even during the middle of the Depression.

After her third marriage ended in 1934, Harlow met William Powell, another MGM star, and quickly fell in love. The couple were reportedly engaged for two years,[68] but differences that ranged from past marriages to Powell's uncertainty about the future, kept them from publicly formalizing their relationship.[69] The two co-starred in her next film Reckless (1935), her first movie musical; her voice was dubbed with that of vocalist Virginia Verrill.

Suzy (1936), in which she played the title role, gave her top billing over four time co-star Tone and Cary Grant. While critics noted that Harlow dominated the film, it was a reasonable box-office success. She then starred in Riffraff (1936) a financial disappointment that co-starred Spencer Tracy and Una Merkel. Afterwards the release of worldwide hit Libeled Lady (1936), in which she was top-billed over Powell, Loy, and Tracy, brought good reviews for Harlow's comedic performance. During the filming, Jean Harlow was involved with William Powell while Spencer Tracy was having an affair with Myrna Loy.[70][71][72][73] She then filmed W.S. Van Dyke's comedy Personal Property (1937), co-starring Robert Taylor. It was Harlow's final completed motion picture appearance.[74]

Illness and death

[edit]

In January 1937, Harlow and Robert Taylor traveled to Washington, D.C., to take part in fundraising activities associated with Franklin D. Roosevelt's birthday, for the organization later known as the March of Dimes.[79][80] Harlow, a Democrat, had campaigned for Roosevelt in the 1936 United States presidential election, and two years earlier for Upton Sinclair in the 1934 California gubernatorial election.[81][82] The trip was physically taxing for Harlow, and she contracted influenza. She recovered in time to attend the Academy Awards ceremony with William Powell.[74]

Filming for Harlow's final film, Saratoga, co-starring Clark Gable, was scheduled to begin in March 1937. However, production was delayed when she developed sepsis after a multiple wisdom tooth extraction, and had to be hospitalized. Almost two months later, Harlow recovered, and shooting began on April 22, 1937.[83] She also appeared on the May 3 cover of Life magazine in photographs by Martin Munkácsi.[84]

On May 20, 1937, while filming Saratoga, Harlow began to complain of illness. Her symptoms—fatigue, nausea, fluid retention and abdominal pain—did not seem very serious to the studio doctor, who believed that she was suffering from cholecystitis and influenza. The doctor was not aware that Harlow had been ill during the previous year with a severe sunburn and influenza.[85] Friend and co-star Una Merkel noticed Harlow's on-set weight gain, gray pallor and fatigue.[86]

On May 29, while Harlow filmed a scene in which her character had a fever, she was clearly sicker than her character and leaned against her co-star Gable between takes and said, "I feel terrible! Get me back to my dressing room." She requested that the assistant director telephone William Powell, who immediately left his own movie set, in order to escort her back home.[87]

The next day, Powell checked on Harlow and discovered that her condition had not improved. He contacted her mother and insisted that she cut her holiday short to be at her daughter's side. Powell also summoned a doctor.[87] Because Harlow's previous illnesses had delayed the shooting of three movies (Wife vs. Secretary, Suzy, and Libeled Lady), initially there was no great concern regarding this latest bout with a recurring illness. On June 2, it was announced she was again suffering from influenza.[88] Ernest Fishbaugh, who had been called to Harlow's home to treat her, diagnosed her with an inflamed gallbladder.[89] Mother Jean told MGM that Harlow was feeling better on June 3, and co-workers expected her back on the set by Monday, June 7, 1937.[90] Press reports were contradictory, with headlines reading "Jean Harlow seriously ill" and "Harlow recovers from illness crisis".[91] When she did not return to set, a concerned Gable visited her and later remarked that she was severely bloated and that he smelled urine on her breath when he kissed her—both signs of kidney failure.[89][92]

Leland Chapman, a colleague of Fishbaugh, was called in to give a second opinion on Harlow's condition. Chapman recognized that she was not suffering from an inflamed gallbladder, but was in the final stages of kidney failure.[93][89] On June 6, 1937, Harlow said that she could not see Powell clearly and could not tell how many fingers he was holding up.[94]

That evening, she was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles, where she slipped into a coma.[95] The next day at 11:37 a.m., Harlow died in the hospital at the age of 26. In the doctor's press releases, the cause of death was given as cerebral edema, a complication of kidney failure.[96] Hospital records mention uremia.[97]

For years, rumors circulated about Harlow's death. Some claimed that her mother had refused to call a doctor because she was a Christian Scientist or that Harlow had declined hospital treatment or surgery.[98] From the onset of her illness, Harlow had been attended by a doctor while she was resting at home. Two nurses also visited her house, and various equipment was brought from a nearby hospital.[99] Harlow's grayish complexion, recurring illnesses, and severe sunburn were signs of the disease.[100] Toxins also adversely affected her brain and central nervous system.[100]

Harlow suffered from scarlet fever when she was 15, and speculation that she suffered a poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis following the incident, which may have caused high blood pressure and ultimately kidney failure, has been suggested.[101] Her death certificate lists the cause of death as "acute respiratory infection", "acute nephritis", and "uremia".[102]

One MGM writer later said, "The day Baby died...there wasn't one sound in the commissary for three hours."[103] Frequent costar Spencer Tracy wrote in his diary, "Jean Harlow died. Grand girl."[104]

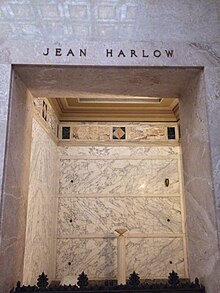

Harlow was interred in the Great Mausoleum at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale in a private room of multicolored marble, which William Powell bought for $25,000 (equivalent to approximately $529,861 in 2023[17] dollars).[105] She was laid to rest in the pink negligee she'd worn in Saratoga and in her hands she had a white gardenia along with a note that Powell had written: "Goodnight, my dearest darling." Harlow's inscription on her crypt reads, "Our Baby".[106]

Spaces in the same room were reserved for Harlow's mother and Powell.[105] Harlow's mother was buried there in 1958, but Powell married actress Diana Lewis in 1940. After his death in 1984, he was cremated[107] and his ashes buried in Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City, California.

MGM planned to replace Harlow in Saratoga with either Jean Arthur or Virginia Bruce, but because of public objections, the film was finished using three doubles (Mary Dees for close-ups, Geraldine Dvorak for long shots, and Paula Winslowe for dubbing Harlow's lines) and rewriting some scenes without her.[108] The film was released on July 23, 1937, less than two months after Harlow's death, and was a hit with audiences,[109][110] grossing $3.3 million in worldwide rentals[111] and becoming the highest-grossing film of the year, as well as the highest-grossing film of Jean Harlow's career.

Legacy

[edit]

According to Camille Paglia, the notion that blondes have more fun was started in Hollywood by Harlow. Pagilia noted "The woman who really started all this in Hollywood was Jean Harlow, with that platinum blonde look which was so incredibly unnatural. With her it was associated with being a harlot — she was mimicking the slouchy, louche look of someone who's a machine for pleasure."[112]

She is noted to have inspired Marilyn Monroe, Madonna and others.[113][114][115]

Her name was given to a cocktail, the "Jean Harlow", which is equal parts light rum and sweet vermouth.[116][117]

Blues musician Lead Belly wrote the song "Jean Harlow" while in prison upon hearing about her death.[118]

The French composer Charles Koechlin composed the piece Épitaphe de Jean Harlow (opus 164) in 1937.[119]

On February 8, 1960, Jean Harlow was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame located at 6910 Hollywood Boulevard on the south part of the Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles, California.[120]

Kim Carnes's hit "Bette Davis Eyes" (1981) contains the line "her hair is Harlow gold."[121]

Harlow's signature, hands and footprints were imprinted in cement on September 29, 1933, in the 24th ceremony at Grauman's Chinese Theater and are located near the forecourt on the west side of the box office at 6925 Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood, California.[122][123]

Novel

[edit]Harlow wrote a novel titled Today Is Tonight. In Arthur Landau's introduction to the 1965 paperback edition, Harlow stated around 1933–1934 her intention to write the book, but it was not published during her lifetime. During her life, Harlow's stepfather Marino Bello shopped the unpublished manuscript to a few studios.[124] Louis B. Mayer, head of MGM, prevented the book from being sold by putting an injunction on it using a clause in Harlow's contract: her services as an artist couldn't be used without MGM's permission.[124] After her death, Landau wrote, her mother sold the film rights to MGM, though no film was made. The publication rights were passed from Harlow's mother to a family friend, and the book was finally published in 1965.[125]

Film portrayals

[edit]Film adaptations of Harlow's life were considered at different times during the 1950s. Twentieth Century-Fox had slated Jayne Mansfield for the role, and ideas for Columbia Pictures actress Cleo Moore to play Harlow were also tabled. These projects never materialized. Marilyn Monroe was given a role for Harlow in 1953, but she declined it, feeling it was under-developed.[126]

In 1965, two films about Jean Harlow were released, both titled Harlow. The first film was released by Magna Corporation in May 1965, and starred Carol Lynley.[127] The second film was released in June 1965 by Paramount Pictures, and starred Carroll Baker.[128] Both were poorly received, and did not perform well at the box office.[129]

In 1975, Roberta Collins played Harlow in the rhythm-and-blues band Bloodstone's pop musical movie Train Ride to Hollywood.[130]

In 1978, Lindsay Bloom portrayed her in Hughes and Harlow: Angels in Hell.[131]

In August 1993, Sharon Stone hosted a documentary about Harlow titled Harlow: The Blonde Bombshell, which aired on Turner Classic Movies.[132]

In 2004, Gwen Stefani briefly appeared as Harlow at the red carpet premiere for Hell's Angels in Martin Scorsese's Howard Hughes biopic The Aviator.[133]

Filmography

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ McDonald, Paul (2012). Hollywood Stardom. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118321669.

- ^ Parish, Mank & Stanke 1978, p. 192.

- ^ Flynn, Jane (1992). Kansas City Women of Independent Minds. Kansas City, MO: Fifield Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-9633-7580-3. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Golden 1991, p. 123.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 9, 12–13.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 14.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 17.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 18.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 25.

- ^ Neibaur, James L. (March 28, 2019). The Jean Harlow Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-7484-1.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b c 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Neibaur, James L. (March 28, 2019). The Jean Harlow Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3602-3.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 30.

- ^ a b Neibaur, James L. (March 28, 2019). The Jean Harlow Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-7484-1.

- ^ a b Stenn 1993, pp. 30–33.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 34.

- ^ "Biography". Jean Harlow. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Higham, Charles (September 24, 2013). Howard Hughes: The Secret Life. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4668-5315-7.

- ^ Barlett, Donald L.; Steele, James B. (April 11, 2011). Howard Hughes: His Life and Madness. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07858-9.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 34–38.

- ^ Barlett, Donald L.; Steele, James B. (1979). Empire: The Life, Legend and Madness of Howard Hughes. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-3930-7513-7.

- ^ a b Stenn 1993, pp. 42, 46–47.

- ^ Pitkin 2008, p. 134: "... premier on May 27, 1930 was extravagant even by Hollywood standards. ... but the critics were merciless, The New Yorker reporting “Jean Harlow is plain awful. ... working on loan from Hughes to M-G-M and Universal studios: The Secret ..."

- ^ "Chaplin's "City Lights" shine in Criterion edition". The Virginian-Pilot. Norfolk. November 27, 2013. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Jean Harlow in CITY LIGHTS". Discovering Chaplin. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 54–57.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 59.

- ^ "Mobster Who Made Millions as Rum-Runner Hangs Self". Albuquerque Journal. February 27, 1959. p. 33. Retrieved October 29, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Target of Crime Probes Found Hanged in Mansion". Greeley Daily Tribune. Associated Press. February 26, 1959. p. 24. Retrieved October 30, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Longy Zwillman". Old Newark.

- ^ a b Conrad 1999, p. 46.

- ^ Sabini, Lou (June 6, 2017). Sex In the Cinema: The Pre-Code Years (1929–1934). BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-6293-3106-5.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Schwarcz, Joe (October 16, 2020). "The Right Chemistry: How Jean Harlow became a 'platinum blond'". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Sherrow 2006, p. 200.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 67–71.

- ^ Parish, Mank & Stanke 1978, p. 203.

- ^ Gragg, Larry D. (January 16, 2015). Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel: The Gangster, the Flamingo, and the Making of Modern Las Vegas: The Gangster, the Flamingo, and the Making of Modern Las Vegas. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-0186-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Edelman, Diana (July 25, 2012). "The daughter of Las Vegas: an interview with Bugsy Siegel's daughter, Millicent". d travels 'round. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ World's Greatest True Crime. Barnes & Noble. January 7, 2018. ISBN 978-0-7607-5467-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Munn, Michael (March 1, 2013). Jimmy Stewart: The Truth Behind the Legend. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-6287-3495-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Balio, Tino (March 14, 2018). MGM. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-3174-2967-8.

- ^ Wayne 2002, p. 208.

- ^ Golden, Eve (December 1, 2000). Golden Images: 41 Essays on Silent Film Stars. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0834-4.

- ^ Ankerich, Michael G. (December 4, 2011). The Sound of Silence: Conversations with 16 Film and Stage Personalities (reprint ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7864-8534-5.

- ^ Jordan 2009, p. 213.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Blodgett, Lucy (October 30, 2011). "Hollywood Ghost Stories For A Haunted Halloween". HuffPost. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ Fleming, E.J. (2009). Paul Bern: The Life and Famous Death of the MGM Director and Husband of Harlow. McFarland. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-7864-3963-8.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 114–115.

- ^ "Jean Harlow and Harold Rosson (1933)". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 130–31.

- ^ McLean, Adrienne L. (December 16, 2010). Glamour in a Golden Age: Movie Stars of the 1930s. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-5233-0.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 167–69.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 183–87.

- ^ Nash & Ross 1988, p. 3848.

- ^ "The Death of Jean Harlow". June 22, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Bryant, Roger (December 9, 2014). William Powell: The Life and Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5493-8.

- ^ William Powell: The Life and Films (2006) - Roger Bryant - p.116

- ^ The leading men of MGM, Jane Ellen Wayne, éditions First Carroll and Graf editions 2005, page 209

- ^ An affair to Remember-the remarkable love story of Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, Christopher Andersen, éditions William Morrow and Co 1997, page 85-86

- ^ "Libeled Lady". Variety. January 1, 1936. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Wayne 2002, p. 118.

- ^ "January 30th, 1937". FDR: Day by Day. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ "My Day by Eleanor Roosevelt, February 1, 1937". Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project at George Washington University. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Jean Harlow at Franklin D. Roosevelt's 55th birthday party, January 30, 1937 on YouTube

- ^ "Combating an Epidemic: President Roosevelt's Birthday Celebrations on January 30". Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Roosevelt, Eleanor (February 1, 1937). "My Day". The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. George Washington University. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ "Jean Harlow, In Washington for the President's Ball, Kisses a Senator". Life. Vol. 2, no. 7. February 15, 1937. p. 38. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ Platinum Girl: The Life and Legends of Jean Harlow; Eve Golden, 1991

- ^ Hollywood, Politics and Society; Mark Wheeler, 2019

- ^ Spicer 2002, pp. 155–156.

- ^ "Cover". Life. Vol. 2, no. 18. May 3, 1937.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 194, 207–208.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 207.

- ^ a b Golden 1991, p. 208.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 226.

- ^ a b c Pitkin 2008, p. 138.

- ^ Golden 1991, p. 210.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 277.

- ^ Murtaugh, Taysha (September 19, 2017). "What Most People Don't Know About Jean Harlow's Death at 26 Years Old". Country Living. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Orci, Taylor (February 22, 2013). "The Original 'Blonde Bombshell' Used Actual Bleach on Her Head". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Pitkin 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Golden 1991, p. 201.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 211, 214.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 355.

- ^ Parish, Mank & Stanke 1978, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 225–226.

- ^ a b Golden 1991, pp. 208–210.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Jean Harlow death certificate, autopsyfiles.org; accessed November 12, 2016.

- ^ Golden 1991, p. 211.

- ^ @harlowheaven (June 9, 2020). "Spencer Tracy, who wrote this in his personal journal two days previous: "Jean Harlow died—Grand girl—"" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Golden 1991, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Stenn 1993, p. 239.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Golden 1991, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Nash & Ross 1988, p. 2740.

- ^ Monush 2003, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Glancy, H. Mark (1992). "MGM film grosses, 1924–1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 12 (2): 127–144. doi:10.1080/01439689200260081.

- ^ Guilbert, G.C. (2015). Madonna as Postmodern Myth: How One Star's Self-Construction Rewrites Sex, Gender, Hollywood and the American Dream. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-7864-8071-5. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Madonna: The Ultimate Compendium of Interviews, Articles, Facts and Opinions From the Files of Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone Series. Hyperion. 1997. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7868-8154-3. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ "Jean Harlow, the Hollywood Actress Who Inspired Marilyn Monroe". Vintage Everyday. April 25, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Carrasco, Isabel (August 30, 2019). "Jean Harlow, The Actress Who Inspired Marilyn Monroe By Breaking Gender Taboos". Cultura Colectiva. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Graham, Colleen. "Classic Jean Harlow Cocktail Recipe". Thespruce.com. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "How To Make A Jean Harlow Cocktail". Made Man. May 2, 2010. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Chilton, Martin (June 15, 2015). "Lead Belly: the musician who influenced a generation". The Daily Telegraph. London. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ Orledge, Robert (1989). Charles Koechlin (1867–1950): His Life and Works. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-3-7186-0609-2.

- ^ "Jean Harlow". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ "Story of the song: Bette Davis Eyes by Kim Carnes". The Independent. November 11, 2022. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ Amburn, Ellis (September 1, 2018). Olivia de Havilland and the Golden Age of Hollywood. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4930-3410-9.

- ^ "Imprint Ceremonies Archive". TCL Chinese Theatre. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Neibaur, James L. (March 28, 2019). The Jean Harlow Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-7484-1.

- ^ Sheppard, Eugenia (June 22, 1965). "Harlow Novel Leaves No Eye Dry". The Montreal Gazette. p. 20. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Neibaur, James L. (March 28, 2019). The Jean Harlow Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3602-3.

- ^ "Harlow Story Filmed". Spokane Daily Chronicle. May 12, 1965. p. 12. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Dunning, Bruce (July 15, 1965). "Carol Clobbers Carrol In Area 'Harlow' Sweepstakes". St. Petersburg Times. p. 5-D. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Parish p. 238

- ^ Szebin, Frederick C. (October 1998). "Roberta Collins:'Caged Heat'! Diary of a Drive-In Diva:Partyin' and Bustin'-Out with Pam Grier". Femme Fatales. Baltimore, Maryland: King Features Syndicate, Inc. p. 46. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jean Harlow Portrayer". Reading Eagle. May 5, 1977. p. 43. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Grahnke, Lon (August 13, 1993). "Stone Honors Career, Tragic Life of Jean Harlow". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 63.

- ^ "Gwen Stefani". Entertainment Weekly. June 14, 2004. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

Sources

[edit]- Barlett, Donald L.; Steele, James B. (1979). Empire: The Life, Legend and Madness of Howard Hughes. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-3930-7513-7.

- Block, Alex Ben; Autrey Wilson, Lucy (2010). George Lucas's Blockbusting: A Decade-by-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-196345-2.

- Conrad, Barnaby (1999). The Blonde: A Celebration of the Golden Era from Harlow to Monroe. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-2591-7.

- Eyman, Scott (2005). Lion of Hollywood : the life and legend of Louis B. Mayer. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-0481-1.

- Fleming, E.J. (January 9, 2009). Paul Bern: The Life and Famous Death of the MGM Director and Husband of Harlow. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-3963-8.

- Fleming, E. J. (2004). The fixers : Eddie Mannix, Howard Strickling, and the MGM publicity machine. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-2027-8.

- Golden, Eve (1991). Platinum Girl: The Life and Legends of Jean Harlow. Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-1-5585-9214-8.

- Jordan, Jessica Hope (2009). The Sex Goddess in American Film, 1930–1965: Jean Harlow, Mae West, Lana Turner, and Jayne Mansfield. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1-60497-663-2.

- Monush, Barry, ed. (2003). Screen World Presents the Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors: From the Silent Era to 1965. Vol. 1. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-5578-3551-2.

- Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph (1988). The Motion Picture Guide (7th ed.). Cinebooks. ISBN 978-0-9339-9716-5.

- Parish, James Robert; Mank, Gregory W.; Stanke, Don E. (1978). The Hollywood Beauties. Arlington House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8700-0412-4.

- Pitkin, Roy (2008). Whom the Gods Love Die Young: A Modern Medical Perspective on Illnesses that Caused the Early Death of Famous People. Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4349-9199-7.

- Sherrow, Victoria, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-3133-3145-9.

- Shulman, Irving (1964). Harlow, an Intimate Biography. Bernard Geis Associates via: Random House. OCLC 7006652.

- Spicer, Chrystopher J. (January 15, 2002). Clark Gable: Biography, Filmography, Bibliography. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1124-5.

- Stenn, David (1993). Bombshell: The Life and Death of Jean Harlow. New York: Bentam Doubleday Dell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-3854-2157-7.

- Wayne, Jane Ellen (2002). The Golden Girls of MGM. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-1303-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Pascal, John. The Jean Harlow Story. Popular Library. 1964.

- Viera, Mark A.; Darrel, Rooney. Harlow in Hollywood: The Blonde Bombshell in the Glamour Capital, 1928–1937. Angel City Press. 2011.

- Longworth, Karina (October 20, 2015). "MGM Stories Part Six: Jean Harlow". You Must Remember This.

- Pinals, Robert S.; Golden, Eve (March 2012). "A Hollywood Mystery: The Untimely Death of Jean Harlow" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 18 (2): 106–108. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182480247. PMID 22367693.

External links

[edit]- 1911 births

- 1937 deaths

- 20th-century American actresses

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American women writers

- Actresses from Kansas City, Missouri

- Actresses from Los Angeles

- American film actresses

- American silent film actresses

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- Deaths from kidney failure in California

- Infectious disease deaths in California

- Lake Forest Academy alumni

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players

- California Democrats

- Missouri Democrats