Hathor

| Hathor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Composite image of Hathor's most common iconography, based partly on images from the tomb of Nefertari | |||

| Name in hieroglyphs | Egyptian: ḥwt-ḥr

| ||

| Major cult center | |||

| Parents | Ra | ||

| Consort | |||

| Offspring | Ihy, Neferhotep of Hu, Ra (Cycle Of Rebirth), Horus (In some myths) | ||

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Hathor (Ancient Egyptian: ḥwt-ḥr, lit. 'House of Horus', Ancient Greek: Ἁθώρ Hathōr, Coptic: ϩⲁⲑⲱⲣ, Meroitic: 𐦠𐦴𐦫𐦢 Atari) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god Ra, both of whom were connected with kingship, and thus she was the symbolic mother of their earthly representatives, the pharaohs. She was one of several goddesses who acted as the Eye of Ra, Ra's feminine counterpart, and in this form, she had a vengeful aspect that protected him from his enemies. Her beneficent side represented music, dance, joy, love, sexuality, and maternal care, and she acted as the consort of several male deities and the mother of their sons. These two aspects of the goddess exemplified the Egyptian conception of femininity. Hathor crossed boundaries between worlds, helping deceased souls in the transition to the afterlife.

Hathor was often depicted as a cow, symbolizing her maternal and celestial aspect, although her most common form was a woman wearing a headdress of cow horns and a sun disk. She could also be represented as a lioness, a cobra, or a sycomore tree.

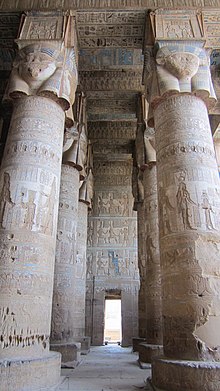

Cattle goddesses similar to Hathor were portrayed in Egyptian art in the fourth millennium BC, but she may not have appeared until the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC). With the patronage of Old Kingdom rulers, she became one of Egypt's most important deities. More temples were dedicated to her than to any other goddess; her most prominent temple was Dendera in Upper Egypt. She was also worshipped in the temples of her male consorts. The Egyptians connected her with foreign lands, such as Nubia and Canaan, and their valuable goods, such as incense and semiprecious stones, and some of the peoples in those lands adopted her worship. In Egypt, she was one of the deities commonly invoked in private prayers and votive offerings, particularly by women desiring children.

During the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC), goddesses such as Mut and Isis encroached on Hathor's position in royal ideology, but she remained one of the most widely worshipped deities. After the end of the New Kingdom, Hathor was increasingly overshadowed by Isis, but she continued to be venerated until the extinction of ancient Egyptian religion in the early centuries AD.

Origins

[edit]

Images of cattle appear frequently in the artwork of Predynastic Egypt (before c. 3100 BC), as do images of women with upraised, curved arms, reminiscent of the shape of bovine horns. Both types of imagery may represent goddesses connected with cattle.[2] Cows are venerated in many cultures, including ancient Egypt, as symbols of motherhood and nourishment, because they care for their calves and provide humans with milk. The Gerzeh Palette, a stone palette from the Naqada II period of prehistory (c. 3500–3200 BC), shows the silhouette of a cow's head with inward-curving horns surrounded by stars. The palette suggests that this cow was also linked with the sky, as were several goddesses from later times who were represented in this form: Hathor, Mehet-Weret, and Nut.[3]

Despite these earlier precedents, Hathor is not unambiguously mentioned or depicted until the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2613–2494 BC) of the Old Kingdom,[4] although several artifacts that refer to her may date to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BC).[5] When Hathor does clearly appear, her horns curve outward, rather than inward like those in Predynastic art.[6]

A bovine deity with inward-curving horns appears on the Narmer Palette from near the start of Egyptian history, both atop the palette and on the belt or apron of the king, Narmer. The Egyptologist Henry George Fischer suggested this deity may be Bat, a goddess who was later depicted with a woman's face and inward-curling horns, seemingly reflecting the curve of the cow horns.[6] The Egyptologist Lana Troy, however, identifies a passage in the Pyramid Texts from the late Old Kingdom that connects Hathor with the "apron" of the king, reminiscent of the goddess on Narmer's garments, and suggests the goddess on the Narmer Palette is Hathor rather than Bat.[4][7]

In the Fourth Dynasty, Hathor rose rapidly to prominence.[8] She supplanted an early crocodile god who was worshipped at Dendera in Upper Egypt to become Dendera's patron deity, and she increasingly absorbed the cult of Bat in the neighboring region of Hu, so that in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) the two deities fused into one.[9] The theology surrounding the pharaoh in the Old Kingdom, unlike that of earlier times, focused heavily on the sun god Ra as king of the gods and father and patron of the earthly king. Hathor ascended with Ra and became his mythological wife, and thus divine mother of the pharaoh.[8]

Roles

[edit]Hathor took many forms and appeared in a wide variety of roles.[10] The Egyptologist Robyn Gillam suggests that these diverse forms emerged when the royal goddess promoted by the Old Kingdom court subsumed many local goddesses worshipped by the general populace, who were then treated as manifestations of her.[11] Egyptian texts often speak of the manifestations of the goddess as "Seven Hathors"[10] or, less commonly, of many more Hathors—as many as 362.[12] For these reasons, Gillam calls her "a type of deity rather than a single entity".[11] Hathor's diversity reflects the range of traits that the Egyptians associated with goddesses. More than any other deity, she exemplifies the Egyptian perception of femininity.[13]

Sky goddess

[edit]Hathor was given the epithets "mistress of the sky" and "mistress of the stars", and was said to dwell in the sky with Ra and other sun deities. Egyptians thought of the sky as a body of water through which the sun god sailed, and they connected it with the waters from which, according to their creation myths, the sun emerged at the beginning of time. This cosmic mother goddess was often represented as a cow. Hathor and Mehet-Weret were both thought of as the cow who birthed the sun god and placed him between her horns. Like Nut, Hathor was said to give birth to the sun god each dawn.[14]

Hathor's Egyptian name was ḥwt-ḥrw[15] or ḥwt-ḥr.[16] It is typically translated "house of Horus" but can also be rendered as "my house is the sky".[17] The falcon god Horus represented, among other things, the sun and sky. The "house" referred to may be the sky in which Horus lives, or the goddess's womb from which he, as a sun god, is born each day.[18]

Solar goddess

[edit]Hathor was a solar deity, a feminine counterpart to sun gods such as Horus and Ra, and was a member of the divine entourage that accompanied Ra as he sailed through the sky in his barque.[18] She was commonly called the "Golden One", referring to the radiance of the sun, and texts from her temple at Dendera say "her rays illuminate the whole earth."[19] She was sometimes fused with another goddess, Nebethetepet, whose name can mean "Lady of the Offering", "Lady of Contentment",[20] or "Lady of the Vulva".[21] At Ra's cult center of Heliopolis, Hathor-Nebethetepet was worshipped as his consort,[22] and the Egyptologist Rudolf Anthes argued that Hathor's name referred to a mythical "house of Horus" at Heliopolis that was connected with the ideology of kingship.[23]

She was one of many goddesses to take the role of the Eye of Ra, a feminine personification of the disk of the sun and an extension of Ra's own power. Ra was sometimes portrayed inside the disk, which Troy interprets as meaning that the eye goddess was thought of as a womb, from which the sun god was born. Hathor's seemingly contradictory roles as mother, wife, and daughter of Ra reflected the daily cycle of the sun. At sunset the god entered the body of the sky goddess, impregnating her and fathering the deities born from her womb at sunrise: himself and the eye goddess, who would later give birth to him. Ra gave rise to his daughter, the eye goddess, who in turn gave rise to him, her son, in a cycle of constant regeneration.[24]

The Eye of Ra protected the sun god from his enemies and was often represented as a uraeus, or rearing cobra, or as a lioness.[25] A form of the Eye of Ra known as "Hathor of the Four Faces", represented by a set of four cobras, was said to face in each of the cardinal directions to watch for threats to the sun god.[26] A group of myths, known from the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC) onward, describe what happens when the Eye goddess rampages uncontrolled. In the funerary text known as the Book of the Heavenly Cow, Ra sends Hathor as the Eye of Ra to punish humans for plotting rebellion against his rule. She becomes the lioness goddess Sekhmet and massacres the rebellious humans, but Ra decides to prevent her from killing all humanity. He orders that beer be dyed red and poured out over the land. The Eye goddess drinks the beer, mistaking it for blood, and in her inebriated state reverts to being the benign and beautiful Hathor.[27] Related to this story is the myth of the Distant Goddess, from the Late and Ptolemaic periods. The Eye goddess, sometimes in the form of Hathor, rebels against Ra's control and rampages freely in a foreign land: Libya west of Egypt or Nubia to the south. Weakened by the loss of his Eye, Ra sends another god, such as Thoth, to bring her back to him.[28] Once pacified, the goddess returns to become the consort of the sun god or of the god who brings her back.[29] The two aspects of the Eye goddess—violent and dangerous versus beautiful and joyful—reflected the Egyptian belief that women, as the Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown puts it, "encompassed both extreme passions of fury and love".[27]

Music, dance, and joy

[edit]

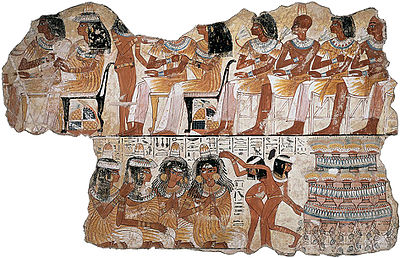

Egyptian religion celebrated the sensory pleasures of life, believed to be among the gods' gifts to humanity. Egyptians ate, drank, danced, and played music at their religious festivals. They perfumed the air with flowers and incense. Many of Hathor's epithets link her to celebration; she is called the mistress of music, dance, garlands, myrrh, and drunkenness. In hymns and temple reliefs, musicians play tambourines, harps, lyres, and sistra in Hathor's honor.[31] The sistrum, a rattle-like instrument, was particularly important in Hathor's worship. Sistra had erotic connotations and, by extension, alluded to the creation of new life.[32]

These aspects of Hathor were linked with the myth of the Eye of Ra. The Eye was pacified by beer in the story of the Destruction of Mankind. In some versions of the Distant Goddess myth, the wandering Eye's wildness abated when she was appeased with products of civilization like music, dance, and wine. The water of the annual flooding of the Nile, colored red by sediment, was likened to wine, and to the red-dyed beer in the Destruction of Mankind. Festivals during the inundation therefore incorporated drink, music, and dance as a way to appease the returning goddess.[33] A text from the Temple of Edfu says of Hathor, "the gods play the sistrum for her, the goddesses dance for her to dispel her bad temper."[34] A hymn to the goddess Raet-Tawy as a form of Hathor at the temple of Medamud describes the Festival of Drunkenness (Tekh Festival) as part of her mythic return to Egypt.[35] Women carry bouquets of flowers, drunken revelers play drums, and people and animals from foreign lands dance for her as she enters the temple's festival booth. The noise of the celebration drives away hostile powers and ensures the goddess will remain in her joyful form as she awaits the male god of the temple, her mythological consort Montu, whose son she will bear.[36]

Sexuality, beauty, and love

[edit]Hathor's joyful, ecstatic side indicates her feminine, procreative power. In some creation myths she helped produce the world itself.[37] Atum, a creator god who contained all things within himself, was said to have produced his children Shu and Tefnut, and thus begun the process of creation, by masturbating. The hand he used for this act, the Hand of Atum, represented the female aspect of himself and could be personified by Hathor, Nebethetepet, or another goddess, Iusaaset.[38] In a late creation myth from the Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BC), the god Khonsu is put in a central role, and Hathor is the goddess with whom Khonsu mates to enable creation.[39]

Hathor could be the consort of many male gods, of whom Ra was only the most prominent. Mut was the usual consort of Amun, the preeminent deity during the New Kingdom who was often linked with Ra. But Mut was rarely portrayed alongside Amun in contexts related to sex or fertility, and in those circumstances, Hathor or Isis stood at his side instead.[40] In the late periods of Egyptian history, the form of Hathor from Dendera and the form of Horus from Edfu were considered husband and wife[41] and in different versions of the myth of the Distant Goddess, Hathor-Raettawy was the consort of Montu[42] and Hathor-Tefnut the consort of Shu.[43]

Hathor's sexual side was seen in some short stories. In a cryptic fragment of a Middle Kingdom story, known as "The Tale of the Herdsman", a herdsman encounters a hairy, animal-like goddess in a marsh and reacts with terror. On another day he encounters her as a nude, alluring woman. Most Egyptologists who study this story think this woman is Hathor or a goddess like her, one who can be wild and dangerous or benign and erotic. Thomas Schneider interprets the text as implying that between his two encounters with the goddess the herdsman has done something to pacify her.[44] In "The Contendings of Horus and Set", a New Kingdom short story about the dispute between those two gods, Ra is upset after being insulted by another god, Babi, and lies on his back alone. After some time, Hathor exposes her genitals to Ra, making him laugh and get up again to perform his duties as ruler of the gods. Life and order were thought to be dependent on Ra's activity, and the story implies that Hathor averted the disastrous consequences of his idleness. Her act may have lifted Ra's spirits partly because it sexually aroused him, although why he laughed is not fully understood.[45]

Hathor was praised for her beautiful hair. Egyptian literature contains allusions to a myth not clearly described in any surviving texts, in which Hathor lost a lock of hair that represented her sexual allure. One text compares this loss with Horus's loss of his divine Eye and Set's loss of his testicles during the struggle between the two gods, implying that the loss of Hathor's lock was as catastrophic for her as the maiming of Horus and Set was for them.[46]

Hathor was called "mistress of love", as an extension of her sexual aspect. In the series of love poems from Papyrus Chester Beatty I, from the Twentieth Dynasty (c. 1189–1077 BC), men and women ask Hathor to bring their lovers to them: "I prayed to her [Hathor] and she heard my prayer. She destined my mistress [loved one] for me. And she came of her own free will to see me."[47]

Motherhood and queenship

[edit]

Hathor was considered the mother of various child deities. As suggested by her name, she was often thought of as both Horus's mother and consort.[48] As both the king's wife and his heir's mother, Hathor was the divine counterpart of human queens.[15]

Isis and Osiris were considered Horus's parents in the Osiris myth as far back as the late Old Kingdom, but the relationship between Horus and Hathor may be older still. If so, Horus only came to be linked with Isis and Osiris as the Osiris myth emerged during the Old Kingdom.[49] Even after Isis was firmly established as Horus's mother, Hathor continued to appear in this role, especially when nursing the pharaoh. Images of the Hathor-cow with a child in a papyrus thicket represented his mythological upbringing in a secluded marsh. Goddesses' milk was a sign of divinity and royal status. Thus, images in which Hathor nurses the pharaoh represent his right to rule.[50] Hathor's relationship with Horus gave a healing aspect to her character, as she was said to have restored Horus's missing eye or eyes after Set attacked him.[18] In the version of this episode in "The Contendings of Horus and Set", Hathor finds Horus with his eyes torn out and heals the wounds with gazelle's milk.[51]

Beginning in the Late Period (664–323 BC), temples focused on the worship of a divine family: an adult male deity, his wife, and their immature son. Satellite buildings, known as mammisis, were built in celebration of the birth of the local child deity. The child god represented the cyclical renewal of the cosmos and an archetypal heir to the kingship.[52] Hathor was the mother in many of these local divine triads. At Dendera, the mature Horus of Edfu was the father and Hathor the mother, while their child was Ihy, a god whose name meant "sistrum-player" and who personified the jubilation associated with the instrument.[53] At Kom Ombo, Hathor's local form, Tasenetnofret, was mother to Horus's son Panebtawy.[54] Other children of Hathor included a minor deity from the town of Hu, named Neferhotep,[53] and several child forms of Horus.[55]

The milky sap of the sycamore tree, which the Egyptians regarded as a symbol of life, became one of her symbols.[56] The milk was equated with water of the Nile inundation and thus fertility.[57] In the late Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, many temples contained a creation myth that adapted long-standing ideas about creation.[58] The version from Hathor's temple at Dendera emphasizes that she, as a female solar deity, was the first being to emerge from the primordial waters that preceded creation, and her life-giving light and milk nourished all living things.[59]

Hathor's maternal aspects can be compared with those of Isis and Mut, yet there are many contrasts between them. Isis's devotion to her husband and care for their child represented a more socially acceptable form of love than Hathor's uninhibited sexuality,[60] and Mut's character was more authoritative than sexual.[61] The text of the 1st century CE Insinger Papyrus likens a faithful wife, the mistress of a household, to Mut, while comparing Hathor to a strange woman who tempts a married man.[61]

Fate

[edit]Like Meskhenet, another goddess who presided over birth, Hathor was connected with shai, the Egyptian concept of fate, particularly when she took the form of the Seven Hathors. In two New Kingdom works of fiction, the "Tale of Two Brothers" and the "Tale of the Doomed Prince", the Hathors appear at the births of major characters and foretell the manner of their deaths. The Egyptians tended to think of fate as inexorable. Yet in "The Tale of the Doomed Prince", the prince who is its protagonist is able to escape one of the possible violent deaths that the Seven Hathors have foretold for him, and while the end of the story is missing, the surviving portions imply that the prince can escape his fate with the help of the gods.[62]

Foreign lands and goods

[edit]Hathor was connected with trade and foreign lands, possibly because her role as a sky goddess linked her with stars and hence navigation,[63] and because she was believed to protect ships on the Nile and in the seas beyond Egypt as she protected the barque of Ra in the sky.[64] The mythological wandering of the Eye goddess in Nubia or Libya gave her a connection with those lands as well.[65]

Egypt maintained trade relations with the coastal cities of Syria and Canaan, particularly Byblos, placing Egyptian religion in contact with the religions of that region.[66] At some point, perhaps as early as the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians began to refer to the patron goddess of Byblos, Baalat Gebal, as a local form of Hathor.[67] So strong was Hathor's link to Byblos that texts from Dendera say she resided there.[68] The Egyptians sometimes equated Anat, an aggressive Canaanite goddess who came to be worshipped in Egypt during the New Kingdom, with Hathor.[69] Some Canaanite artworks depict a nude goddess with a curling wig taken from Hathor's iconography.[70] Which goddess these images represent is not known, but the Egyptians adopted her iconography and came to regard her as an independent deity, Qetesh,[71] whom they associated with Hathor.[72]

Hathor was closely connected with the Sinai Peninsula,[73] which was not considered part of Egypt proper but was the site of Egyptian mines for copper, turquoise, and malachite during the Middle and New Kingdoms.[74] One of Hathor's epithets, "Lady of Mefkat", may have referred specifically to turquoise or to all blue-green minerals. She was also called "Lady of Faience", a blue-green ceramic that Egyptians likened to turquoise.[75][76] Hathor was also worshipped at various quarries and mining sites in Egypt's Eastern Desert, such as the amethyst mines of Wadi el-Hudi, where she was sometimes called "Lady of Amethyst".[77]

South of Egypt, Hathor's influence was thought to have extended over the land of Punt, which lay along the Red Sea coast and was a major source for the incense with which Hathor was linked, as well as with Nubia, northwest of Punt.[64] The autobiography of Harkhuf, an official in the Sixth Dynasty (c. 2345–2181 BC), describes his expedition to a land in or near Nubia, from which he brought back great quantities of ebony, panther skins, and incense for the king. The text describes these exotic goods as Hathor's gift to the pharaoh.[73] Egyptian expeditions to mine gold in Nubia introduced her cult to the region during the Middle and New Kingdoms,[78] and New Kingdom pharaohs built several temples to her in the portions of Nubia that they ruled.[79]

Afterlife

[edit]

Although the Pyramid Texts, the earliest Egyptian funerary texts, rarely mention her,[80] Hathor was invoked in private tomb inscriptions from the same era, and in the Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts and later sources, she is frequently linked with the afterlife.[81]

Just as she crossed the boundary between Egypt and foreign lands, Hathor passed through the boundary between the living and the Duat, the realm of the dead.[82] She helped the spirits of deceased humans enter the Duat and was closely linked with tomb sites, where that transition began.[83] The necropolises, or clusters of tombs, on the west bank of the Nile were personified as Imentet, the goddess of the west, who was frequently regarded as a manifestation of Hathor.[84] The Theban necropolis, for example, was often portrayed as a stylized mountain with the cow of Hathor emerging from it.[85] Her role as a sky goddess was also linked to the afterlife. Because the sky goddess—either Nut or Hathor—assisted Ra in his daily rebirth, she had an important part in ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs, according to which deceased humans were reborn like the sun god.[86] Coffins, tombs, and the underworld itself were interpreted as the womb of this goddess, from which the deceased soul would be reborn.[87][88]

Nut, Hathor, and Imentet could each, in different texts, lead the deceased into a place where they would receive food and drink for eternal sustenance. Thus, Hathor, as Imentet, often appears on tombs, welcoming the deceased person as her child into a blissful afterlife.[89] In New Kingdom funerary texts and artwork, the afterlife was often illustrated as a pleasant, fertile garden, over which Hathor sometimes presided.[90] The welcoming afterlife goddess was often portrayed as a goddess in the form of a tree, giving water to the deceased. Nut most commonly filled this role, but the tree goddess was sometimes called Hathor instead.[91]

The afterlife also had a sexual aspect. In the Osiris myth, the murdered god Osiris was resurrected when he copulated with Isis and conceived Horus. In solar ideology, Ra's union with the sky goddess allowed his own rebirth. Sex therefore enabled the rebirth of the deceased, and goddesses like Isis and Hathor served to rouse the deceased to new life. But they merely stimulated the male deities' regenerative powers, rather than playing the central role.[92]

Ancient Egyptians prefixed the names of the deceased with Osiris's name to connect them with his resurrection. For example, a woman named Henutmehyt would be dubbed "Osiris-Henutmehyt". Over time they increasingly associated the deceased with both male and female divine powers.[93] As early as the late Old Kingdom, women were sometimes said to join the worshippers of Hathor in the afterlife, just as men joined the following of Osiris. In the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–664 BC), Egyptians began to add Hathor's name to that of deceased women in place of that of Osiris. In some cases, women were called "Osiris-Hathor", indicating that they benefited from the revivifying power of both deities. In these late periods, Hathor was sometimes said to rule the afterlife as Osiris did.[94]

Iconography

[edit]Hathor was often depicted as a cow bearing the sun disk between her horns, especially when shown nursing the king. She could also appear as a woman with the head of a cow. Her most common form, however, was a woman wearing a headdress of the horns and sun disk, often with a red or turquoise sheath dress, or a dress combining both colors. Sometimes the horns stood atop a low modius or the vulture headdress that Egyptian queens often wore in the New Kingdom. Because Isis adopted the same headdress during the New Kingdom, the two goddesses can be distinguished only if labeled in writing. When in the role of Imentet, Hathor wore the emblem of the west upon her head instead of the horned headdress.[95] The Seven Hathors were sometimes portrayed as a set of seven cows, accompanied by a minor sky and afterlife deity called the Bull of the West.[96]

Some animals other than cattle could represent Hathor. The uraeus was a common motif in Egyptian art and could represent a variety of goddesses who were identified with the Eye of Ra.[97] When Hathor was depicted as a uraeus, it represented the ferocious and protective aspects of her character. She also appeared as a lioness, and this form had a similar meaning.[98] In contrast, the domestic cat, which was sometimes connected with Hathor, often represented the Eye goddess's pacified form.[99] When portrayed as a sycamore tree, Hathor was usually shown with the upper body of her human form emerging from the trunk.[100]

Like other goddesses, Hathor might carry a stalk of papyrus as a staff, though she could instead hold a was staff, a symbol of power that was usually restricted to male deities.[76] The only goddesses who used the was were those, like Hathor, who were linked with the Eye of Ra.[101] She also commonly carried a sistrum or a menat necklace. The sistrum came in two varieties: a simple loop shape or the more complex naos sistrum, which was shaped to resemble a naos shrine and flanked by volutes resembling the antennae of the Bat emblem.[102] Mirrors were another of her symbols, because in Egypt they were often made of gold or bronze and therefore symbolized the sun disk, and because they were connected with beauty and femininity. Some mirror handles were made in the shape of Hathor's face.[103] The menat necklace, made up of many strands of beads, was shaken in ceremonies in Hathor's honor, similarly to the sistrum.[73] Images of it were sometimes seen as personifications of Hathor herself.[104]

Hathor was sometimes represented as a human face with bovine ears, seen from the front rather than in the profile-based perspective that was typical of Egyptian art. When she appears in this form, the tresses on either side of her face often curl into loops. This mask-like face was placed on the capitals of columns beginning in the late Old Kingdom. Columns of this style were used in many temples to Hathor and other goddesses.[105] These columns have two or four faces, which may represent the duality between different aspects of the goddess or the watchfulness of Hathor of the Four Faces. The designs of Hathoric columns have a complex relationship with those of sistra. Both styles of sistrum can bear the Hathor mask on the handle, and Hathoric columns often incorporate the naos sistrum shape above the goddess's head.[102]

-

Statue of Hathor, fourteenth century BC

-

Naos sistrum with Hathor's face, 305–282 BC

-

Mirror with a face of Hathor on the handle, fifteenth century BC

-

Head of Hathor with cats on her headdress, from a clapper, late second to early first millennium BC

-

The Malqata Menat necklace, fourteenth century BC

-

Hathoric capital from the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, fifteenth century BC

Worship

[edit]

Relationship with royalty

[edit]During the Early Dynastic Period, Neith was the preeminent goddess at the royal court,[106] while in the Fourth Dynasty, Hathor became the goddess most closely linked with the king.[66] Sneferu, the founder of the Fourth Dynasty, may have built a temple to her, and Neferhetepes, a daughter of Djedefra, was the first recorded priestess of Hathor.[107] Old Kingdom rulers donated resources only to temples dedicated to particular kings or to deities closely connected with kingship. Hathor was one of the few deities to receive such donations.[108] Late Old Kingdom rulers especially promoted the cult of Hathor in the provinces, as a way of binding those regions to the royal court. She may have absorbed the traits of contemporary provincial goddesses.[109]

Many female royals, though not reigning queens, held positions in the cult during the Old Kingdom.[110] Mentuhotep II, who became the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom despite having no relation to the Old Kingdom rulers, sought to legitimize his rule by portraying himself as Hathor's son. The first images of the Hathor-cow suckling the king date to his reign, and several priestesses of Hathor were depicted as though they were his wives, although he may not have actually married them.[111][112] In the course of the Middle Kingdom, queens were increasingly seen as directly embodying the goddess, just as the king embodied Ra.[113] The emphasis on the queen as Hathor continued through the New Kingdom. Queens were portrayed with the headdress of Hathor beginning in the late Eighteenth Dynasty. An image of the sed festival of Amenhotep III, meant to celebrate and renew his rule, shows the king together with Hathor and his queen Tiye, which could mean that the king symbolically married the goddess in the course of the festival.[114]

Hatshepsut, a woman who ruled as a pharaoh in the early New Kingdom, emphasized her relationship to Hathor in a different way.[115] She used names and titles that linked her to a variety of goddesses, including Hathor, so as to legitimize her rule in what was normally a male position.[116] She built several temples to Hathor and placed her own mortuary temple, which incorporated a chapel dedicated to the goddess, at Deir el-Bahari, which had been a cult site of Hathor since the Middle Kingdom.[115]

The preeminence of Amun during the New Kingdom gave greater visibility to his consort Mut, and in the course of the period, Isis began appearing in roles that traditionally belonged to Hathor alone, such as that of the goddess in the solar barque. Despite the growing prominence of these deities, Hathor remained important, particularly in relation to fertility, sexuality, and queenship, throughout the New Kingdom.[117]

After the New Kingdom, Isis increasingly overshadowed Hathor and other goddesses as she took on their characteristics.[118] In the Ptolemaic period (305–30 BC), when Greeks governed Egypt and their religion developed a complex relationship with that of Egypt, the Ptolemaic dynasty adopted and modified the Egyptian ideology of kingship. Beginning with Arsinoe II, wife of Ptolemy II, the Ptolemies closely linked their queens with Isis and with several Greek goddesses, particularly their own goddess of love and sexuality, Aphrodite.[119] Nevertheless, when the Greeks referred to Egyptian gods by the names of their own gods (a practice called interpretatio graeca), they sometimes called Hathor Aphrodite.[120] Traits of Isis, Hathor, and Aphrodite were all combined to justify the treatment of Ptolemaic queens as goddesses. Thus, the poet Callimachus alluded to the myth of Hathor's lost lock of hair in the Aetia when praising Berenice II for sacrificing her own hair to Aphrodite,[46] and iconographic traits that Isis and Hathor shared, such as the bovine horns and vulture headdress, appeared on images portraying Ptolemaic queens as Aphrodite.[121]

Temples in Egypt

[edit]

More temples were dedicated to Hathor than to any other Egyptian goddess.[82] During the Old Kingdom her most important center of worship was in the region of Memphis, where "Hathor of the Sycamore" was worshipped at many sites throughout the Memphite Necropolis. During the New Kingdom era, the temple of Hathor of the Southern Sycamore was her main temple in Memphis.[122] At that site she was described as the daughter of the city's main deity, Ptah.[86] The cult of Ra and Atum at Heliopolis, northeast of Memphis, included a temple to Hathor-Nebethetepet that was probably built in the Middle Kingdom. A willow and a sycamore tree stood near the sanctuary and may have been worshipped as manifestations of the goddess.[22] A few cities farther north in the Nile Delta, such as Yamu and Terenuthis, also had temples to her.[123]

Dendera, Hathor's oldest temple in Upper Egypt, dates to at least to the Fourth Dynasty.[124] After the end of the Old Kingdom it surpassed her Memphite temples in importance.[125] Many kings made additions to the temple complex through Egyptian history. The last version of the temple was built in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and is today one of the best-preserved Egyptian temples from that time.[126]

As the rulers of the Old Kingdom made an effort to develop towns in Upper and Middle Egypt, several cult centers of Hathor were founded across the region, at sites such as Cusae, Akhmim, and Naga ed-Der.[127] In the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC) her cult statue from Dendera was periodically carried to the Theban necropolis. During the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, Mentuhotep II established a permanent cult center for her in the necropolis at Deir el-Bahari.[128] The nearby village of Deir el-Medina, home to the tomb workers of the necropolis during the New Kingdom, also contained temples of Hathor. One continued to function and was periodically rebuilt as late as the Ptolemaic Period, centuries after the village was abandoned.[129]

In the Old Kingdom, most priests of Hathor, including the highest ranks, were women. Many of these women were members of the royal family.[130] In the course of the Middle Kingdom, women were increasingly excluded from the highest priestly positions, at the same time that queens were becoming more closely tied to Hathor's cult. Thus, non-royal women disappeared from the high ranks of Hathor's priesthood,[131] although women continued to serve as musicians and singers in temple cults across Egypt.[132]

The most frequent temple rite for any deity was the daily offering ritual, in which the cult image, or statue, of a deity would be clothed and given food.[133] The daily ritual was largely the same in every Egyptian temple,[133] although the goods given as offerings could vary according to which deity received them.[134] Wine and beer were common offerings in all temples, but especially in rituals in Hathor's honor,[135] and she and the goddesses related to her often received sistra and menat necklaces.[134] In Late and Ptolemaic times, they were also offered a pair of mirrors, representing the sun and the moon.[136]

Festivals

[edit]Many of Hathor's annual festivals were celebrated with drinking and dancing that served a ritual purpose. Revelers at these festivals may have aimed to reach a state of religious ecstasy, which was otherwise rare or nonexistent in ancient Egyptian religion. Graves-Brown suggests that celebrants in Hathor's festivals aimed to reach an altered state of consciousness to allow them interact with the divine realm.[137] An example is the Festival of Drunkenness, commemorating the return of the Eye of Ra, which was celebrated on the twentieth day of the month of Thout at temples to Hathor and to other Eye goddesses. It was celebrated as early as the Middle Kingdom, but it is best known from Ptolemaic and Roman times.[137] The dancing, eating and drinking that took place during the Festival of Drunkenness represented the opposite of the sorrow, hunger, and thirst that the Egyptians associated with death. Whereas the rampages of the Eye of Ra brought death to humans, the Festival of Drunkenness celebrated life, abundance, and joy.[138]

In a local Theban festival known as the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, which began to be celebrated in the Middle Kingdom, the cult image of Amun from the Temple of Karnak visited the temples in the Theban Necropolis while members of the community went to the tombs of their deceased relatives to drink, eat, and celebrate.[139] Hathor was not involved in this festival until the early New Kingdom,[140] after which Amun's overnight stay in the temples at Deir el-Bahari came to be seen as his sexual union with her.[141]

Several temples in Ptolemaic times, including that of Dendera, observed the Egyptian new year with a series of ceremonies in which images of the temple deity were supposed to be revitalized by contact with the sun god. On the days leading up to the new year, Dendera's statue of Hathor was taken to the wabet, a specialized room in the temple, and placed under a ceiling decorated with images of the sky and sun. On the first day of the new year, the first day of the month of Thoth, the Hathor image was carried up to the roof to be bathed in genuine sunlight.[142]

The best-documented festival focused on Hathor is another Ptolemaic celebration, the Festival of the Beautiful Reunion. It took place over fourteen days in the month of Epiphi.[143][144] Hathor's cult image from Dendera was carried by boat to several temple sites to visit the gods of those temples. The endpoint of the journey was the Temple of Horus at Edfu, where the Hathor statue from Dendera met that of Horus of Edfu and the two were placed together.[145] On one day of the festival, these images were carried out to a shrine where primordial deities such as the sun god and the Ennead were said to be buried. The texts say the divine couple performed offering rites for these entombed gods.[146] Many Egyptologists regard this festival as a ritual marriage between Horus and Hathor, although Martin Stadler challenges this view, arguing that it instead represented the rejuvenation of the buried creator gods.[147] C. J. Bleeker thought the Beautiful Reunion was another celebration of the return of the Distant Goddess, citing allusions in the temple's festival texts to the myth of the solar eye.[148] Barbara Richter argues that the festival represented all three things at once. She points out that the birth of Horus and Hathor's son Ihy was celebrated at Dendera nine months after the Festival of the Beautiful Reunion, implying that Hathor's visit to Horus represented Ihy's conception.[149]

The third month of the Egyptian calendar, Hathor or Athyr, was named for the goddess. Festivities in her honor took place throughout the month, although they are not recorded in the texts from Dendera.[150]

Worship outside Egypt

[edit]

Egyptian kings as early as the Old Kingdom donated goods to the temple of Baalat Gebal in Byblos, using the syncretism of Baalat with Hathor to cement their close trading relationship with Byblos.[151] A temple to Hathor as Lady of Byblos was built during the reign of Thutmose III, although it may simply have been a shrine within the temple of Baalat.[152] After the breakdown of the New Kingdom, Hathor's prominence in Byblos diminished along with Egypt's trade links to the city. A few artifacts from the early first millennium BC suggest that the Egyptians began equating Baalat with Isis at that time.[153] A myth about Isis's presence in Byblos, related by the Greek author Plutarch in his work On Isis and Osiris in the 2nd century AD, suggests that by his time Isis had entirely supplanted Hathor in the city.[154]

A pendant found in a Mycenaean tomb at Pylos, from the 16th century BC, bears Hathor's face. Its presence in the tomb suggests the Mycenaeans may have known that the Egyptians connected Hathor with the afterlife.[155]

Egyptians in the Sinai Peninsula built a few temples in the region. The largest was a complex dedicated primarily to Hathor as patroness of mining at Serabit el-Khadim, on the west side of the peninsula.[156] It was occupied from the middle of the Middle Kingdom to near the end of the New.[157] The Timna Valley, on the fringes of the Egyptian empire on the east side of the peninsula, was the site of seasonal mining expeditions during the New Kingdom. It included a shrine to Hathor that was probably deserted during the off-season. The local Midianites, whom the Egyptians used as part of the mining workforce, may have given offerings to Hathor as their overseers did. After the Egyptians abandoned the site in the Twentieth Dynasty, however, the Midianites converted the shrine to a tent shrine devoted to their own deities.[158]

In contrast, the Nubians in the south fully incorporated Hathor into their religion. During the New Kingdom, when most of Nubia was under Egyptian control, pharaohs dedicated several temples in Nubia to Hathor, such as those at Faras and Mirgissa.[79] Amenhotep III and Ramesses II both built temples in Nubia that celebrated their respective queens as manifestations of female deities, including Hathor: Amenhotep's wife Tiye at Sedeinga[159] and Ramesses's wife Nefertari at the Small Temple of Abu Simbel.[160] The independent Kingdom of Kush, which emerged in Nubia after the collapse of the New Kingdom, based its beliefs about Kushite kings on the royal ideology of Egypt. Therefore, Hathor, Isis, Mut, and Nut were all seen as the mythological mother of each Kushite king and equated with his female relatives, such as the kandake, the Kushite queen or queen mother, who had prominent roles in Kushite religion.[161] At Jebel Barkal, a site sacred to Amun, the Kushite king Taharqa built a pair of temples, one dedicated to Hathor and one to Mut as consorts of Amun, replacing New Kingdom Egyptian temples that may have been dedicated to these same goddesses.[162] But Isis was the most prominent of the Egyptian goddesses worshipped in Nubia, and her status there increased over time. Thus, in the Meroitic period of Nubian history (c. 300 BC – AD 400), Hathor appeared in temples mainly as a companion to Isis.[163]

Popular worship

[edit]

In addition to formal and public rituals at temples, Egyptians privately worshipped deities for personal reasons, including at their homes. Birth was hazardous for both mother and child in ancient Egypt, yet children were much desired. Thus fertility and safe childbirth are among the most prominent concerns in popular religion, and fertility deities such as Hathor and Taweret were commonly worshipped in household shrines. Egyptian women squatted on bricks while giving birth, and the only known surviving birth brick from ancient Egypt is decorated with an image of a woman holding her child flanked by images of Hathor.[164] In Roman times, terracotta figurines, sometimes found in a domestic context, depicted a woman with an elaborate headdress exposing her genitals, as Hathor did to cheer up Ra.[165] The meaning of these figurines is not known,[166] but they are often thought to represent Hathor or Isis combined with Aphrodite making a gesture that represented fertility or protection against evil.[165]

Hathor was one of a handful of deities, including Amun, Ptah, and Thoth, who were commonly prayed to for help with personal problems.[167] Many Egyptians left offerings at temples or small shrines dedicated to the gods they prayed to. Most offerings to Hathor were used for their symbolism, not for their intrinsic value. Cloths painted with images of Hathor were common, as were plaques and figurines depicting her animal forms. Different types of offerings may have symbolized different goals on the part of the donor, but their meaning is usually unknown. Images of Hathor alluded to her mythical roles, like depictions of the maternal cow in the marsh.[168] Offerings of sistra may have been meant to appease the goddess's dangerous aspects and bring out her positive ones,[169] while phalli represented a prayer for fertility, as shown by an inscription found on one example.[170]

Some Egyptians also left written prayers to Hathor, inscribed on stelae or written as graffiti.[167] Prayers to some deities, such as Amun, show that they were thought to punish wrongdoers and heal people who repented for their misbehavior. In contrast, prayers to Hathor mention only the benefits she could grant, such as abundant food during life and a well-provisioned burial after death.[171]

Funerary practices

[edit]

As an afterlife deity, Hathor appeared frequently in funerary texts and art. In the early New Kingdom, for instance, she was one of the three deities most commonly found in royal tomb decoration, the others being Osiris and Anubis.[172] In that period she often appeared as the goddess welcoming the dead into the afterlife.[173] Other images referred to her more obliquely. Reliefs in Old Kingdom tombs show men and women performing a ritual called "shaking the papyrus". The significance of this rite is not known, but inscriptions sometimes say it was performed "for Hathor", and shaking papyrus stalks produces a rustling sound that may have been likened to the rattling of a sistrum.[174] Other Hathoric imagery in tombs included the cow emerging from the mountain of the necropolis[85] and the seated figure of the goddess presiding over a garden in the afterlife.[90] Images of Nut were often painted or incised inside coffins, indicating the coffin was her womb, from which the occupant would be reborn in the afterlife. In the Third Intermediate Period, Hathor began to be placed on the floor of the coffin, with Nut on the interior of the lid.[88]

Tomb art from the Eighteenth Dynasty often shows people drinking, dancing, and playing music, as well as holding menat necklaces and sistra—all imagery that alluded to Hathor. These images may represent private feasts that were celebrated in front of tombs to commemorate the people buried there, or they may show gatherings at temple festivals such as the Beautiful Festival of the Valley.[175] Festivals were thought to allow contact between the human and divine realms, and by extension, between the living and the dead. Thus, texts from tombs often expressed a wish that the deceased would be able to participate in festivals, primarily those dedicated to Osiris.[176] Tombs' festival imagery, however, may refer to festivals involving Hathor, such as the Festival of Drunkenness, or to the private feasts, which were also closely connected with her. Drinking and dancing at these feasts may have been meant to intoxicate the celebrants, as at the Festival of Drunkenness, allowing them to commune with the spirits of the deceased.[175]

Hathor was said to supply offerings to deceased people as early as the Old Kingdom, and spells to enable both men and women to join her retinue in the afterlife appeared as early as the Coffin Texts.[94] Some burial goods that portray deceased women as goddesses may depict these women as followers of Hathor, although whether the imagery refers to Hathor or Isis is not known. The link between Hathor and deceased women was maintained into the Roman Period, the last stage of ancient Egyptian religion before its extinction.[177]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hart 2005, p. 61.

- ^ Hassan 1992, p. 15.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 1999, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Gillam 1995, p. 214.

- ^ a b Fischer 1962, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Troy 1986, p. 54.

- ^ a b Lesko 1999, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Fischer 1962, pp. 7, 14–15.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2003, pp. 77, 145.

- ^ a b Gillam 1995, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Troy 1986, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, pp. 31–34, 46–47.

- ^ a b Graves-Brown 2010, p. 130.

- ^ Billing 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, pp. 25, 48.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson 2003, p. 140.

- ^ Richter 2016, pp. 128, 184–185.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 156.

- ^ Pinch 1993, p. 155.

- ^ a b Quirke 2001, pp. 102–105.

- ^ Gillam 1995, p. 218.

- ^ Troy 1986, pp. 21–23, 25–27.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Ritner 1990, p. 39.

- ^ a b Graves-Brown 2010, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 71–74.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 130.

- ^ Harrington 2016, pp. 132–134.

- ^ Finnestad 1999, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Manniche 2010, pp. 13–14, 16–17.

- ^ Poo 2009, pp. 153–157.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, p. 57.

- ^ Darnell 1995, p. 48.

- ^ Darnell 1995, pp. 54, 62, 91–94.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 138.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 99, 141, 156.

- ^ Cruz-Uribe 1994, pp. 185, 187–188.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 155.

- ^ Lesko 1999, p. 127.

- ^ Darnell 1995, pp. 47, 69.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 197.

- ^ Schneider 2007, pp. 315–317.

- ^ Morris 2007, pp. 198–199, 201, 207.

- ^ a b Selden 1998, pp. 346–348.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 183–184.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2003, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 123, 168.

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Roberts 2000, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Richter 2016, pp. 179–182.

- ^ McClain 2011, pp. 3–6.

- ^ Richter 2016, pp. 169–172, 185.

- ^ Griffiths 2001, p. 189.

- ^ a b te Velde 2001, p. 455.

- ^ Hoffmeier 2001, pp. 507–508.

- ^ Hollis 2020, p. 53.

- ^ a b Bleeker 1973, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Darnell 1995, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b Hollis 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Espinel 2002, pp. 117–119.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 139.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 137.

- ^ Cornelius 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Cornelius 2004, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Hart 2005, p. 65.

- ^ Pinch 1993, p. 52.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Espinel 2005, pp. 61, 65–66.

- ^ Yellin 2012, pp. 125–128.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2000, pp. 227–230.

- ^ Hollis 2020, p. 48.

- ^ Smith 2017, pp. 251–252.

- ^ a b Graves-Brown 2010, p. 166.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 88, 164.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b Pinch 1993, pp. 179–180.

- ^ a b Vischak 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Assmann 2005, pp. 170–173.

- ^ a b Lesko 1999, pp. 39–40, 110.

- ^ Assmann 2005, pp. 152–154, 170–173.

- ^ a b Billing 2004, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Billing 2004, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Cooney 2010, pp. 227–229.

- ^ Cooney 2010, pp. 227–229, 235–236.

- ^ a b Smith 2017, pp. 251–254.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 143–144, 148.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 77, 175.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Roberts 1997, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 190–197.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Graham 2001, p. 166.

- ^ a b Pinch 1993, pp. 153–159.

- ^ Wilkinson 1993, pp. 32, 83.

- ^ Pinch 1993, p. 278.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 135–139.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Gillam 1995, p. 215.

- ^ Goedicke 1978, pp. 118–123.

- ^ Morris 2011, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Gillam 1995, pp. 222–226, 231.

- ^ Gillam 1995, p. 231.

- ^ Graves-Brown 2010, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Gillam 1995, p. 234.

- ^ Graves-Brown 2010, pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b Lesko 1999, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Robins 1999, pp. 107–112.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 119–120, 178–179.

- ^ Lesko 1999, p. 129.

- ^ Selden 1998, pp. 312, 339.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 141.

- ^ Cheshire 2007, pp. 157–163.

- ^ Gillam 1995, pp. 219–221.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 108, 111.

- ^ Gillam 1995, p. 227.

- ^ Vischak 2001, p. 83.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Gillam 1995, pp. 226, 229.

- ^ Goedicke 1991, pp. 245, 252.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Gillam 1995, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 243–244.

- ^ a b Thompson 2001, p. 328.

- ^ a b Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 126–128.

- ^ Poo 2010, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Derriks 2001, pp. 421–422.

- ^ a b Graves-Brown 2010, pp. 166–169.

- ^ Frandsen 1999, pp. 131, 142–143.

- ^ Teeter 2011, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Sadek 1988, p. 49.

- ^ Teeter 2011, p. 70.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 193–198.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, p. 93.

- ^ Richter 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, p. 94.

- ^ Verner 2013, pp. 437–439.

- ^ Stadler 2008, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Bleeker 1973, pp. 98–101.

- ^ Richter 2016, pp. 4, 202–205.

- ^ Verner 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Espinel 2002, pp. 116–118.

- ^ Traunecker 2001, p. 110.

- ^ Zernecke 2013, pp. 227–230.

- ^ Hollis 2009, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Lobell 2020.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 59–69.

- ^ Morkot 2012, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Fisher 2012, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Kendall 2010b.

- ^ Kendall 2010a, pp. 1, 12.

- ^ Yellin 2012, pp. 128, 133.

- ^ Ritner 2008, pp. 173–175, 181.

- ^ a b Morris 2007, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Sandri 2012, pp. 637–638.

- ^ a b Pinch 1993, pp. 349–351.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 119, 347, 354–355.

- ^ Pinch 1993, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Lesko 2008, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Sadek 1988, pp. 89, 114–115.

- ^ Lesko 1999, p. 110.

- ^ Assmann 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Woods 2011, pp. 314–316.

- ^ a b Harrington 2016, pp. 132–136, 144–147.

- ^ Assmann 2005, p. 225.

- ^ Smith 2017, pp. 384–389.

Works cited

[edit]- Assmann, Jan (2005) [German edition 2001]. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801442414.

- Billing, Nils (2004). "Writing an Image: The Formulation of the Tree Goddess Motif in the Book of the Dead, Ch. 59". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 32: 35–50. JSTOR 25152905.

- Bleeker, C. J. (1973). Hathor and Thoth: Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian Religion. Brill. ISBN 978-9004037342.

- Cheshire, Wendy A. (2007). "Aphrodite Cleopatra". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 43: 151–191. JSTOR 27801612.

- Cooney, Kathlyn M. (December 2010). "Gender Transformation in Death: A Case Study of Coffins from Ramesside Period Egypt" (PDF). Near Eastern Archaeology. 73 (4): 224–237. doi:10.1086/NEA41103940. JSTOR 41103940. S2CID 166450284. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-04-02.

- Cornelius, Izak (2004). The Many Faces of the Goddess: The Iconography of the Syro-Palestinian Goddesses Anat, Astarte, Qedeshet, and Asherah c. 1500–1000 BCE. Academic Press Fribourg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen. ISBN 978-3727814853, 978-3525530610

- Cruz-Uribe, Eugene (1994). "The Khonsu Cosmogony". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 31: 169–189. doi:10.2307/40000676. JSTOR 40000676.

- Darnell, John Coleman (1995). "Hathor Returns to Medamûd". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 22: 47–94. JSTOR 25152711.

- Derriks, Claire (2001). "Mirrors". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 419–422. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- Espinel, Andrés Diego (2002). "The Role of the Temple of Ba'alat Gebal as Intermediary between Egypt and Byblos during the Old Kingdom". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 30: 103–119. JSTOR 25152861.

- Espinel, Andrés Diego (2005). "A Newly Identified Stela from Wadi el-Hudi (Cairo JE 86119)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 91: 55–70. doi:10.1177/030751330509100104. JSTOR 3822393. S2CID 190217800.

- Finnestad, Ragnhild (1999). "Enjoying the Pleasures of Sensation: Reflections on A Significant Feature of Egyptian Religion" (PDF). In Teeter, Emily; Larson, John A. (eds.). Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 111–119. ISBN 978-1885923097. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-20.

- Fischer, Henry George (1962). "The Cult and Nome of the Goddess Bat". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 1: 7–18. doi:10.2307/40000855. JSTOR 40000855.

- Fisher, Marjorie M. (2012). "Abu Simbel". In Fisher, Marjorie M.; Lacovara, Peter; Ikram, Salima; D'Auria, Sue (eds.). Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile. The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 356–360. ISBN 978-9774164781.

- Frandsen, Paul John (1999). "On Fear of Death and the Three bwts Connected with Hathor" (PDF). In Teeter, Emily; Larson, John A. (eds.). Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 131–148. ISBN 978-1885923097. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-20.

- Gillam, Robyn A. (1995). "Priestesses of Hathor: Their Function, Decline and Disappearance". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 32: 211–237. doi:10.2307/40000840. JSTOR 40000840.

- Goedicke, Hans (1978). "Cult-Temple and 'State' During the Old Kingdom in Egypt". In Lipiński, Edward (ed.). State and Temple Economy in the Ancient Near East. Departement Oriëntalistiek. pp. 113–130. ISBN 978-9070192037.

- Goedicke, Hans (October 1991). "The Prayers of Wakh-ʿankh-antef-ʿAa". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 50 (4): 235–253. doi:10.1086/373513. JSTOR 545487. S2CID 162271458. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Graham, Geoffrey (2001). "Insignias". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 163–167. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- Graves-Brown, Carolyn (2010). Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt. Continuum. ISBN 978-1847250544.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn (2001). "Isis". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 188–191. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- Harrington, Nicola (2016). "The Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian Banquet: Ideals and Realities". In Draycott, Catherine M.; Stamatopolou, Maria (eds.). Dining and Death: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the 'Funerary Banquet' in Ancient Art, Burial and Belief. Peeters. pp. 129–172. ISBN 978-9042932517.

- Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Second Edition. Routledge. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-0203023624.

- Hassan, Fekri A. (1992). "Primeval Goddess to Divine King: The Mythogenesis of Power in the Early Egyptian State". In Friedman, Renee; Adams, Barbara (eds.). The Followers of Horus: Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman. Oxbow Books. pp. 307–319. ISBN 978-0946897445.

- Hoffmeier, James K. (2001). "Fate". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 507–508. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- Hollis, Susan Tower (2009). "Hathor and Isis in Byblos in the Second and First Millennia BCE". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 1 (2). doi:10.2458/azu_jaei_v01i2_tower_hollis. ISSN 1944-2815.

- Hollis, Susan Tower (2020). Five Egyptian Goddesses: Their Possible Beginnings, Actions, and Relationships in the Third Millennium BCE. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-7809-3595-9.

- Kendall, Timothy (2010a). "B 200 and B 300: Temples of the Goddesses Hathor and Mut" (PDF). Jebel Barkal History and Archaeology. National Corporation of Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), Sudan. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- Kendall, Timothy (2010b). "The Napatan Period". Jebel Barkal History and Archaeology. National Corporation of Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), Sudan. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- Lesko, Barbara S. (1999). The Great Goddesses of Egypt. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806132020.

- Lesko, Barbara S. (2008). "Household and Domestic Religion in Egypt". In Bodel, John; Olyan, Saul M. (eds.). Household and Family Religion in Antiquity. Blackwell. pp. 197–209. ISBN 978-1405175791.

- Lobell, Jarrett A. (March–April 2020). "Field of Tombs". Archaeology. 73 (2).

- Manniche, Lise (2010). "The Cultic Significance of the Sistrum in the Amarna Period". In Woods, Alexandra; McFarlane, Ann; Binder, Susanne (eds.). Egyptian Culture and Society: Studies in Honour of Naguib Kanawati. Conseil Suprême des Antiquités de l'Égypte. pp. 13–26. ISBN 978-9774798450.

- McClain, Brett (2011). Wendrich, Willeke (ed.). "Cosmogony (Late to Ptolemaic and Roman Periods)". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. ISBN 978-0615214030. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- Meeks, Dimitri; Favard-Meeks, Christine (1996) [French edition 1993]. Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods. Translated by G. M. Goshgarian. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801431159.

- Morris, Ellen F. (2007). "Sacred and Obscene Laughter in 'The Contendings of Horus and Seth', in Egyptian Inversions of Everyday Life, and in the Context of Cultic Competition". In Schneider, Thomas; Szpakowska, Kasia (eds.). Egyptian Stories: A British Egyptological Tribute to Alan B. Lloyd on the Occasion of His Retirement. Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 197–224. ISBN 978-3934628946.

- Morris, Ellen F. (2011). "Paddle Dolls and Performance". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 47: 71–103. doi:10.7916/D8PK1ZM4. JSTOR 24555386.

- Morkot, Robert G. (2012). "Sedeinga". In Fisher, Marjorie M.; Lacovara, Peter; Ikram, Salima; D'Auria, Sue (eds.). Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile. The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 325–328. ISBN 978-9774164781.

- Pinch, Geraldine (1993). Votive Offerings to Hathor. Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0900416545.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

- Poo, Mu-Chou (2009) [First edition 1995]. Wine and Wine Offering in the Religion of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-0710305015.

- Poo, Mu-Chou (2010). Wendrich, Willeke (ed.). "Liquids in Temple Ritual". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. ISBN 978-0615214030. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- Quirke, Stephen (2001). The Cult of Ra: Sun Worship in Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051078.

- Richter, Barbara A. (2016). The Theology of Hathor of Dendera: Aural and Visual Scribal Techniques in the Per-Wer Sanctuary. Lockwood Press. ISBN 978-1937040512.

- Ritner, Robert K. (1990). "O. Gardiner 363: A Spell Against Night Terrors". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 27: 25–41. doi:10.2307/40000071. JSTOR 40000071.

- Ritner, Robert K. (2008). "Household Religion in Ancient Egypt". In Bodel, John; Olyan, Saul M. (eds.). Household and Family Religion in Antiquity. Blackwell. pp. 171–196. ISBN 978-1405175791.

- Roberts, Alison (1997) [First edition 1995]. Hathor Rising: The Power of the Goddess in Ancient Egypt. Inner Traditions International. ISBN 978-0892816217.

- Roberts, Alison (2000). My Heart My Mother: Death and Rebirth in Ancient Egypt. NorthGate Publishers. ISBN 978-0952423317.

- Robins, Gay (1999). "The Names of Hatshepsut as King". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 85: 103–112. doi:10.1177/030751339908500107. JSTOR 3822429. S2CID 162426276.

- Sadek, Ashraf I. (1988). Popular Religion in Egypt during the New Kingdom. Gerstenber. ISBN 978-3806781076.

- Sandri, Sandra (2012). "Terracottas". In Riggs, Christina (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 630–647. ISBN 978-0199571451.

- Schneider, Thomas (2007). "Contextualising the Tale of the Herdsman". In Schneider, Thomas; Szpakowska, Kasia (eds.). Egyptian Stories: A British Egyptological Tribute to Alan B. Lloyd on the Occasion of His Retirement. Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 309–318. ISBN 978-3934628946.

- Selden, Daniel L. (October 1998). "Alibis" (PDF). Classical Antiquity. 17 (2): 289–412. doi:10.2307/25011086. JSTOR 25011086. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-21.

- Smith, Mark (2017). Following Osiris: Perspectives on the Osirian Afterlife from Four Millennia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199582228.

- Stadler, Martin (2008). Wendrich, Willeke (ed.). "Procession". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. ISBN 978-0615214030. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- Teeter, Emily (2011). Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521613002.

- te Velde, Herman (2001). "Mut" (PDF). In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 454–455. ISBN 978-0195102345. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-24.

- Thompson, Stephen E. (2001). "Cults: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 326–332. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- Traunecker, Claude (2001) [French edition 1992]. The Gods of Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801438349.

- Troy, Lana (1986). Patterns of Queenship in Ancient Egyptian Myth and History. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-9155419196.

- Verner, Miroslav (2013) [Czech edition 2010]. Temple of the World: Sanctuaries, Cults, and Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Anna Bryson-Gustová. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774165634.

- Vischak, Deborah (2001). "Hathor". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–85. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (1993). Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500236635.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051009.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051207.

- Wilkinson, Toby (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-0203024386. Text Version

- Woods, Alexandra (2011). "Zšš wꜣḏ Scenes of the Old Kingdom Revisited" (PDF). In Strudwick, Nigel; Strudwick, Helen (eds.). Old Kingdom: New Perspectives. Egyptian Art and Archaeology 2750–2150 BC. Proceedings of a Conference at the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, May 2009. Oxbow Books. pp. 314–319. ISBN 978-1842174302. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-03.

- Yellin, Janice W. (2012). "Nubian Religion". In Fisher, Marjorie M.; Lacovara, Peter; Ikram, Salima; D'Auria, Sue (eds.). Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile. The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-9774164781.

- Zernecke, Anna Elise (2013). "The Lady of the Titles: The Lady of Byblos and the Search for Her 'True Name'". Die Welt des Orients. 43 (2): 226–242. doi:10.13109/wdor.2013.43.2.226. JSTOR 23608857.

Further reading

[edit]- Allam, Schafik (1963). Beiträge zum Hathorkult (bis zum Ende des mittleren Reiches) (in German). Verlag Bruno Hessling. OCLC 557461557.

- Derchain, Philippe (1972). Hathor Quadrifrons (in French). Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut in het Nabije Oosten. OCLC 917056815.

- Hornung, Erik (1997). Der ägyptische Mythos von der Himmelskuh, 2nd ed (PDF) (in German). Vandehoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3525537374. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-13.

- Posener, Georges (1986). "La légende de la tresse d'Hathor". In Lesko, Leonard H. (ed.). Egyptological Studies in Honour of Richard A. Parker (in French). Brown. pp. 111–117. ISBN 978-0874513219.

- Vandier, Jacques (1964–1966). "Iousâas et (Hathor)-Nébet-Hétépet". Revue d'Égyptologie (in French). 16–18.

External links

[edit] Media related to Hathor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hathor at Wikimedia Commons- Hymns to Hathor : English translation at attalus.org

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. III (9th ed.). 1878. p. 13.